Electronic health records (EHRs) have become a hot topic since passage of the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act in 2009. Although hospitals and many doctors’ practices had been using some form of electronic patient records for several years, HITECH was a carrot-and-stick approach to speeding up and broadening EHR adoption.

Incentive payments were the carrot, but they were backed up by requirements for care-giving organizations to demonstrate “meaningful use” (MU), the stick. Three rules were established by the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONC) and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) that determined eligibility to receive payment for certified EHR purchase, implementation, and utilization. The first rule defined meaningful use. The second rule established the criteria against which EHR vendors would be evaluated. The third and final rule determined how MU certification would occur.

Offsetting the often-cited big-data opportunities for organizations such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the U.S. Department of Homeland Security that near-universal EHR implementation may provide, many doctors and nurses have expressed concern that patient care could suffer in the rush to certification. Indeed, in May 2014, the ONC and CMS issued a further proposed rule “to change the meaningful use timeline and the definition of certified electronic health record technology.”

According to Mandi Bishop, president of FloriDATA Foundation, quoted in a related May 2014 article, “Vendors aren’t ready; no subject matter experts are available to implement upgrades. Products aren’t fully baked. Providers are frustrated.” The article also quoted Tom Leary, vice president of government relations at the Health Information and Management Systems Society, who explained, “The [ONC and CMS] agencies have proposed a new model for the remainder of 2014 that should go a long way toward relieving some of the time crunch eligible professionals and hospitals are experiencing.”1

During the years since 2009, several studies have been conducted to determine the degree to which EHR technology has been accepted by various parts of the medical community. One of these studies examined more than 100 nurses’ perceptions of EHR in intensive care units (ICUs). As the researchers noted, “Because the use of EHR technology by ICU nurses participating in our study is mandatory, continued acceptance of the technology is important…. In this study, we assess ICU nurses’ perceptions of the usefulness of three EHR functionalities: CPOE [computerized physician order entry], eMAR [electronic medication administration record], and nursing documentation flowsheets. Our research question is: Do implementation method, technology usability, and usefulness affect nurses’ acceptance of EHR?”2

Missing Data

For this study, data was collected at both three months and 12 months after EHR implementation. At three months, 121 of the 237 eligible nurses participated (51%) and at 12 months, 161 of 224 (72%). The researchers attributed the higher participation at 12 months to a more active recruitment of nurses for the study. Very few questions were not answered by all participants—the missing data percentage at three months was 2.95% and at 12 months 2.27%.

How missing data is treated can be very important depending on its extent and nature. In this study, the researchers used Little’s missing completely at random (MCAR) test to determine that the missing data most likely was random and no further adjustments to the data were required.

The MCAR terminology was coined by Donald Rubin in 1976 “to describe data where the complete cases are a random sample of the originally identified set of cases. Since the complete cases are representative of the originally identified sample, inferences based on only the complete cases are applicable to the larger sample and the target population. Complete-case analysis for MCAR data provides results that are generalizable to the target population with one caveat—the estimates will be less precise than initially planned by the researcher since a smaller number of cases are used for estimation.”3 Rubin currently is the John L. Loeb Professor of Statistics at Harvard University.

Had the data not been found to be MCAR, then the nurses’ acceptance study researchers could not have determined that “no inputation was required.” That is, they didn’t need to input any data to complete the incomplete sets. Several schemes have been developed to create data with which incomplete records can be completed. Obviously, you cannot know after the fact the input that a study participant might have provided. So, the best that can be done is to determine the range of inputs that is most likely based on the complete data records that you do have.

For the nurses’ acceptance study, the largest amount of missing data (nine responses) occurred in the three-month data for a question that asked participants how many implementation activities they had been involved in. Of the 112 actual respondents, only two nurses had participated in two or more activities, 79 had participated in none, and 23 had some involvement in at least one discussion prior to implementation.

Perhaps the question was even less relevant to these nine nurses than to the 102 that had very little or no involvement leading up to implementation, so the nine nurses simply skipped it. At the other extreme, it’s unlikely that each of the nine nurses had participated in many implementation activities. By assuming that the missing data was MCAR, the researchers could work only with complete records and assume the results were representative of ICU nurses’ attitudes toward EHRs.

Available data

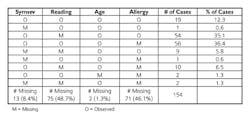

What if more data is missing, and it cannot be claimed to be MCAR? As discussed in reference 3, such data falls into the class of nonignorable missing data, “for which the reasons for the missing observations depend on the values of those variables.” An example in reference 3 of data collected from asthmatic 8- to 14-year-old children had very large amounts of missing data—only 19 of 154 records were complete. In this case, data missing from the 135 incomplete records could not realistically be termed MCAR.

When a portion of the data was presented as shown in the table, a number of possible explanations became apparent. Perhaps data was missing because the lower reading skills of the younger respondents hampered their comprehension of the questions. Perhaps the very condition that qualified a child for inclusion in the study—suffering from asthma and allergies—also hampered his ability to consistently participate. Unless these dependencies were anticipated and incorporated in the data analysis method, the results could be misleading.

Source: A Review of Methods for Missing Data

One common way in which missing data has been provided is to append to incomplete records one or more data points equal to the mean of the complete records. This approach would have very little effect on the nurses’ acceptance study but has huge implications for the asthma study. Even for the nurses’ acceptance study, although the mean would remain unchanged, the standard deviation would not reflect the true limits of the data values.

Another approach is to use all of the available data without attempting to complete the incomplete records. In this case, it is possible that different sets of respondents are associated with different questions. While analyzing the available data for any one question is mathematically valid, comparing or combining responses across multiple questions will not be. In addition, statistics computed on only a small number of responses cannot always be extrapolated to the total population even if the missing data is MCAR.

As summarized in reference 3, “The relative performance of complete-case analysis and available-case analysis, with MCAR data, depends on the correlation between the variables; available-case analysis will provide consistent estimates only when variables are weakly correlated. The major difficulty with available-case analysis lies in the fact that one cannot predict when available-case analysis will provide adequate results, and is thus not useful as a general method.”

References

1. Sullivan, T., “Update: CMS, ONC ease EHR certification requirements for MU,” Government Health IT, May 2014.

2. Carayon, P., et al, “ICU nurses’ acceptance of electronic health records,” Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, 2011.

3. Pigott, T. D., “A Review of Methods for Missing Data,” Educational Research and Evaluation, 2001, Vol. 7, No. 4, pp. 353-383.