Find a downloadable version of this story in pdf format at the end of the story.

Anew Hybrid-switching Method (1) enabled new bridgeless AC-DC converter topologies capable of providing high power factor of 0.99 and low total harmonic distortion of 1.7% as well as galvanic isolation in a single power processing stage resulting in very high efficiencies, reduced size and cost. The Hybrid-switching method results in new DC-DC converter topologies capable of very large voltage step-down and very high efficiencies due to the new Hybrid transformer.NEW STEP-DOWN CONVERTER TOPOLOGY

The new converter topology (2) shown in Fig. 1a consists of three switches, a resonant inductor L r, a resonant capacitor Cr and a hybrid transformer. The two switches S1 and S2 operate out of phase, resulting in two distinct operating intervals: one for ON-time charge interval and another for OFF-time discharge interval. The current rectifier CR is for low voltage applications replaced by a synchronous rectifier MOSFET driven by a direct drive as shown in Fig. 1b. A high-side driver illustrated in Fig. 1b drives the two switches S 1 and S2.

The buck converter and tapped-inductor buck converter are based on the inductive energy storage and transfer only. The converter in Fig. 1a has an additional capacitive energy storage and transfer from input to output through use of hybrid transformer, which results in large voltage step-down at moderate duty ratios and increased efficiency.

BASIC OPERATION

The energy storage and transfer during ON-time interval TON and OFF-time interval TOFF are:

Charge interval (Fig. 2a): The source current during this ON-time interval:

-

Charges the resonant capacitor Cr

-

Stores the inductive energy onto the hybrid transformer magnetizing inductance;

-

Delivers power to the load.

Discharge Interval (Fig. 2b): During this off-time interval:

-

Energy stored in magnetizing inductance is passed to the load.

-

A stored capacitive energy is passed to the load.

We define turns ratio n of the hybrid transformer as:

n =N/N2

(1)

DC VOLTAGE GAIN EVALUATION

The voltage waveform of the hybrid transformer primary winding, N, is shown in Fig. 3a and the voltage waveform of the resonant capacitor C r is shown in Fig. 3b comprising DC voltage V Cr with a superimposed ac ripple voltage πvr . Note that resonant capacitor is charged linearly as in PWM converters during the ON-time interval TON and discharged in a resonant way during the OFF-time interval TOFF (shaded area in Fig. 3b). Note also that the resonant inductor L r is fully flux-balanced during the OFF-time interval only (shaded areas in Fig. 3b). From Fig. 3b, the flux-balance condition on this resonant inductor L r leads to:

VCr - nV = 0

(2)

Flux balance on the hybrid transformer leads to: (Vg - V - VCr ) D TS = VCr (1-D)TS (3)

Replacing (2) into (3) results in:

M = V/ Vg = D/( D + n )

(4)

where:

M = DC voltage gain as a function of the duty ratio, D, and the turns ratio “n”.

The family of the DC voltage gains is shown by graphs in Fig. 4a. Despite the presence of the resonant components, owing to the hybrid-switching method, the dc voltage gain M is only a function of the duty ratio D and the turns ratio “n” and is NOT a funeti of resonant component values nor the load current I as is the case in conventional resonant converters.

Therefore, the output voltage of the converter in Fig. 1b can be regulated against both input voltage and load current changes by the Pulse Width Modulated (PWM) control via duty ratio D.

RESONANT EQUATIONS FOR OFF-TIME INTERVAL

Since the output capacitor C is much larger that the resonant capacitor Cr from the circuit model in Fig. 2b, we deduce the resonant circuit model for the OFF-time interval in Fig. 4b and the solution:

Ir(t) = Im sin ωrt

(5)

Vr(t) = RN Im cos ωrt

(6)

where:

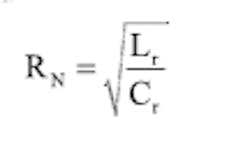

RN= Characteristic impedance

ωr = Radial resonant frequency

fr = Resonant frequency

Tr = resonant period given by:

RESONANT CURRENT AMPLIFICATION BY HYBRID TRANSFORMER

From the circuit model in Fig. 2b the resonant discharge of the capacitor contributes two currents to the load:

i0 = ir + iS

(10)

where:

ir = Resonant inductor current flowing directly to the load

is = Hybrid transformer secondary current

Note how the hybrid transformer in the circuit model of Fig. 2b amplifies the primary current by factor (n- 1) to result in secondary current i S given by:

iS = (n-1) ip

(11)

For the special case when n=2, the primary, the secondary and the output load currents are displayed in Fig 5a. Note that the load current is twice the magnitude of the resonant discharge current. However, the total output current during OFF-time interval has a total charge consisting of 2Qs charge due to inductive discharge to the load and charge 2Q C due to capacitive charge stored in the ON-time interval, which is also released to the load during this OFF-time interval as seen in Fig. 5b. As Q P= QS = QC = Q, the net total charge delivered to the load during both intervals is 5Q, while the input current charge during ON-time interval is Q, resulting in an effective 1 to 5 step-up of DC current from input to output. Therefore, the DC voltage step-down from input to output is 5 to 1. This can be easily realized from Equation (4) for n=2 and D=0.5.

Thus, the hybrid transformer serves the function of the 2:1 voltage step-down (and respective 1:2 currant step-up) for the inductive current flow operating as an autotransformer, but serves in addition as an AC transformer from the primary N1 to secondary side N2 for resonant capacitor discharge current. This is clearly being amplified more when the turns ratio “n” is larger than 2. For example, for n=4, the current amplification is three times from primary N1 to secondary N2 side. Adding also another resonant current directly going to the load results in four times effective capacitor discharge current going into be load. Note also that the autotransformer has on its own four times current amplification from primary to secondary.

Taking the two charge transfers together, the input current (charge) during the OFF-time interval is magnified eight times| on the secondary, which flows to the load. Clearly, this results in the total output charge being nine times larger than input charge for an effective 9:1 DC current conversion ratio from output to input. This corresponds to an effective 9:1 step-down DC voltage conversion ratio, which is easily verified by Equation (4) that for n = 4 and D = 0.5 gives M=1/9 or 9:1 step-down conversion. This will convert input voltage of 12V to l.33V output voltage. Compare this operation at 50% duty ratio to the one required for common buck converter of approximately 0.1 duty ratio. Thus, almost five times smaller duty ratio is required for conventional buck converter to achieve the same 9 to 1 step-down voltage conversion ratio. Note also how the ripple current requirement of the resonant capacitor is only a small fraction of the load current. For this 9 to 1 step-down conversion, resonant capacitor rms current needed is only a fraction of the DC load current. For example, for a 36A load current, the resonant capacitor will only conduct 16/3A of 5.33 A rms current. This can be easily realized by two small multi-layer chip capacitors each rated at 2.7A.

VOLTAGE STRESSES OF THE THREE SWITCHES

From the derived DC currents in all branches one can also derive analytical expressions for the rms currents in various branches so that the conduction losses of the three switches could be calculated. What remains is to determine the voltage stresses of all three switches so that the proper rated switching devices could be selected. From the converter model for OFF-time interval and another one for ON-time interval, the following blocking voltages on three switches can be evaluated:

VS1 = Vg - V

(12)

VS2 = Vg - V

(13)

VS3 = (Vg - V)/n

(14)

MOSFET switches S1 and S2 have slightly lower voltage stresses than the comparable buck converter. However, note in particular the large voltage stress reduction for the MOSFET switch S3 that conducts most of the time for a large step-down. For example, for 12V to 1V conversion and n=4, the blocking voltage of the S3 switch is VS3= 11/ 4 V = 2.75V. This compares with the blocking voltage of 12V for a comparable buck converter or a factor of 4.4 reductions in voltage stress of the switch. If switch S3 is implemented with a planar low voltage technology, the silicon area needed for the same ON-resistance is reduced by a square of the voltage stress ratio.

Hence, instead of 25V technology used for a buck synchronous rectifier MOSFET, a 5V technology can be used to reduce silicon area needed 25 times for a synchronous rectifier MOSFET in the converter of Fig. 1b.

EXPERIMENTAL VERIFICATION

To demonstrate high efficiency, a prototype of a step-down converter in Fig. 1b was built with the following values:

Components:

- MOSFET transistors:

- S1 = 60V; 4.1mΩ

- S2 = 60V; 4.1mΩ

- S3 = 25V; 1.2mΩ (3 in parallel)

- Input capacitor: 8 × 10µF; Output capacitor: 12 × 47µF; Resonant capacitor: 3 × 2.2µF

- Resonant inductor: 2µH (RM4 core); Hybrid transformer: 9:1 turns ratio Lr: 0.65µH (core cross-section 52mm2).

- Resonant and switching frequency: 50kHz

The graph of the efficiency as a function of the load current is shown in Fig. 6 for 48V to 1V and 48V to 1.5V for load currents from 5A to 35A.

By increasing switching frequency from 50kHz to 200kHz, for example, the magnetics size can be correspondingly reduced.

COMPARISON WITH THE TAPPED-INDUCTOR BUCK CONVERTER

The tapped-inductor buck converter (3) does result in reduced output DC voltage compared to the ordinary buck converter for the same duty ratio, D. It also reduces the voltage stress on the synchronous rectifier MOSFET switch by the tapped-inductor turns ratio, “n”. However, all of these advantages are far outweighed by the fundamental problem associated with that converter topology: the energy stored in the leakage inductance of the tapped-inductor must be dissipated, as there is no power path for discharge of that stored energy.

Hence, the larger the step-down turns ratio n of the tapped-inductor and more effective its voltage step-down, the larger is the leakage inductance and more severe leakage inductance loss problem. This stored energy therefore, must be dissipated by using dissipative snubbers and result in large efficiency loss. This loss is also proportional to switching frequency and thus prevents operation at high switching frequencies.

The converter of Fig. 1a, through its additional switch S 2 and the resonant inductor Lr in that branch provides an alternative path to discharge the energy stored on leakage inductance in a non-dissipative resonant manner to the load. Hence, an efficient operation is made possible even at very high switching frequencies needed to make the hybrid transformer small.

An added problem of the tapped-inductor buck converter is that its main switch is floating and cannot be driven with a high-side driver thus requiring a complex transformer-coupled, isolated drive. However, the two switches S1 and S2 in the converter of Fig. 1b are driven by a high-side driver, while the synchronous rectifier MOSFETs can use a direct drive referenced to ground.

COMPARISON WITH THE SYNCHRONOUS BUCK CONVERTER

The synchronous buck converter (3) has the following drawbacks. Large step-down conversion ratios, such as 50 to 1 as in above example requires operation at a very low duty ratio of D=0.02. At switching frequency of 1MHz this would result in ON-time interval of only 20 nsec, which is too small to get a good resolution and reliable DC voltage gain control. The converter of Fig. 1a operates at duty ratios that is at least five times or higher and does not have that problem, so it will be very suitable for conversion from 12V to 0.5V or lower output voltages expected to be standard in near future.

REDUCED TURN-OFF LOSSES

The main input MOSFET switch in the synchronous buck converter has high turn-OFF losses, since its current is higher than the DC load current. The converter in Fig. 1a has the turn-OFF current of switch S1 reduced several times, hence reducing turn-OFF losses. Both switches in synchronous buck mode experience very high frequency ringing spikes due to the uncontrolled nature of the transition from conduction of one switch to the conduction of the other due to commutation of the output inductor current from one switch to the other. This, in turn requires that for a 12V input source the switches must be rated at 25V or higher. Moreover, the passive damping to reduce spikes results in additional losses. These problems are not present in the new converter due to its resonant energy transfer.

In addition, the synchronous MOSFET switch in the new converter has a reduced voltage rating so it could be implemented in a low 5V voltage technology, thus significantly reducing the silicon area needed for its implementation.

Footnote: Hybrid-switching Method™ and Hybrid-Transformer™ are trademarks of TESLAco

Editorial Note: For questions regarding this article and for contact information to the author, readers are directed to TESLAco's Web site www.teslaco.com.

Download the story in pdf format here.

REFERENCES

-

Slobodan Cuk, articles in Power Electronics Technology on Bridgeless PFC converters published in July, August, October and November 2010 issues.

-

Slobodan Cuk, “Step down Converter Having a Resonant Inductor, a Resonant Capacitor and a Hybrid Transformer'', US patent No. 7,914, 874 March 29, 2011, other US and foreign patents pending.

-

Slobodan Cuk and R. D. Middlebrook, “Advances in Switched-Mode Power Conversion vol. I, II, III. TESLAco, 1981 and 1983.