Musician Frank Zappa observed, “Some scientists claim that hydrogen, because it is so plentiful, is the basic building block of the universe. I dispute that. I say there is more stupidity than hydrogen, and that is the basic building block of the universe.” I confess that my own stupidity has been quite plentiful over the years. My only hope is that I am getting less stupid as I age.

Engineering Stupidity

I used to think it was silly that engineering drawings had title blocks that said “Deburr all sharp edges.” It’s just a prototype, I would think, don’t waste time deburring stuff. When I expressed this opinion to a machinist, he shook his head, “It’s my fingers that get cut up. I am the first person that has to handle this thing, and I want it deburred. You should, too. You’re the second person that handles it.”

That taught me about building prototypes and having labels and guards around dangerous things. When fellow engineers or a manager would say “It’s a rush job, don’t bother with any high-voltage guards,” I would think of that machinist and say, “Yeah, but I’m the one developing this and I’m the one most likely to get electrocuted. We will have to wait for the guards.”

It’s Not “Just” a Prototype

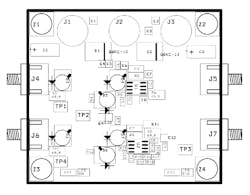

More convenience than safety, but it’s the same thing, with silkscreens on printed circuit boards (PCBs). Bosses would get cheap and tell me to leave off the silkscreen, that “it’s just a prototype.” I explained that’s exactly why I needed the silkscreen. I was the one going to troubleshoot the board and I needed to identify the components. That’s also why I had to argue with other engineers who did not want to back-annotate the reference designators on the PCB (Fig. 1). They wanted the designators to be based on the schematic they drew.

1. After you lay out a PCB board, you should back-annotate it so that the reference designators are in order from top left to bottom right. This allows assemblers to know where to stuff the board, as well as letting you find where a component is located as you read the schematic.

I explained you back-annotate the designators by position on the board, so the assemblers can stuff the board without hunting all over the boards as they work down the bill of materials (BOM). It also lets you find the parts as you debug the board. I know this because I always assembled and tested my first prototypes, and I used to be the stupid engineer that did not back-annotate.

That phrase, “it’s just a prototype,” has caused a lot of stupidity. My friend Russell Gross was an ISO 9000 quality consultant. He never had much trouble getting the factory people doing quality procedures such as calibrating a micrometer. They weren't stupid. The stupidity came in the engineering department.

He told them they need to measure a gauge block with the micrometer, and jot it down on a yellow pad once a year. That was enough to comply with the intent of ISO 9000. The engineers in the lab would bring out that sorry stupid phrase “it’s just a prototype.” Russell would patiently explain, with a prototype, that’s when you need to verify your measuring tools the most. A bad micrometer in the factory might mean a recall. A bad micrometer in the engineering department might mean you could not ship product at all.

Other engineering stupidity is not realizing your job is to verify the documentation for manufacturing. That’s why you get a PCB assembly house to use your “insert” file from your PCB CAD package. That way you know it’s right before it goes into volume production.

I had an intern send out a 19-inch rack front panel for machining. He was proud he got a “deal” from a local shop that was going to make the panel on a hand-crank Bridgeport mill. I explained that we wanted to have it made on a CNC mill with our CAD solid model as the input source. That way we have verified the model was correct. The machinist made a mistake with the Bridgeport, and we got the panel made for free. It was hard to convince the intern that this was not a win. First, we had a defaced panel that looked bad. Second, we had not verified the CAD documentation was correct. It’s never “just” a prototype. A prototype is a sacred object that gets you to manufacturing.

Documentation Stupidity

Another of my stupidities was not being meticulous with documentation. Like most engineers, I hated doing the paperwork. I would make changes on a drawing without changing the revision letter. I didn’t want other people thinking I was stupid by having high revision letters. Turns out, I was exactly being stupid. If you print the drawing or BOM or file, and especially if you give it to others, you have to bump the revision for the next change—no matter how tiny. And every assembly that part is in also gets its revision bumped.

The military contractors I worked for had a great system. Prototypes were given numbered revisions, starting at 01, and up to 99 or even higher. When the part or PCB went to production, it got a letter, “A.” Production changes for long-lived parts often went to double letters, like “AG,” having had more than 26 changes. This way nobody cared if you made dozens of changes to the prototype. The “rev. 99” part would become a rev. A and everyone could feel smart, especially those in management who were smart enough to understand engineering psychology.

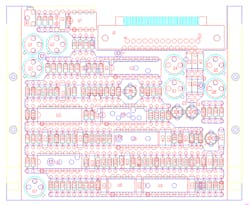

Revision stupidity burned me at Teledyne. We were making radar jamming pods for F-16 fighter planes. The PCBs in one unit had about 120 parts, and lots of hardware (Fig. 2). I did a major redesign of one of the boards. It went up a letter to rev. B, since it was already released to production. I checked out the drawings as an “A” and then turned them back in as a rev. B.

2. This PCB goes in the radar jammer pod of an F-16 fighter jet. With a complete redesign and a simple change of hardware, both getting assigned a revision B, it was the redesign that didn’t happen.

Shortly after, a mechanical engineer wanted to change a single #6-32 washer on the board. He figured it was such a minor change; heck, no reason to log out a new revision and he just turned it back in as a rev. B. Now the document control people had two engineering change orders (ECOs), both making the circuit card assembly (CCA) a revision B. Rather than process the huge one that changes every single part, they did the one that had a single washer change. We are all lazy beings.

The boards went to manufacturing. They were 8-layer boards, at the time costing well over $10,000 each. My new rev. B board came in looking exactly like the rev. A that I had redesigned. The mechanical engineer did not lose his job, but he got a severe tongue lashing, and one that was well deserved. It was not the money the managers cared about as much as the time lost in a useless board spin.

A friend tells of yet another documentation stupidity. He was designing a test board that used a ZIF (zero insertion force) socket. He laid out the board without noticing that the connector manufacturer showed the pin-out drawing from the bottom view, unlike the way IC manufacturers always show the top view. The dozen boards all came in, got assembled, and then had to be scrapped with the very expensive sockets. He had a great observation. When it comes to reading a datasheet, “Every spot of ink matters.” He was professional enough to accept the responsibility, instead of blaming the datasheet. He got smarter from the experience, not angry and bitter.

Another stupid phrase I once used is “you don’t really need that.” I figured I was a smart guy who knew what was needed. When I paid a pal to put in a rebuilt engine in my 1966 Toronado, he noted that, “There was a restrictor in the fuel return line. You really don’t need that. It was stupid they put it in.” The car suffered vapor lock on hot days. I think that’s why the restrictor was there. One thing I have gotten smart about. Billion-dollar multinational manufacturing companies do not just toss in unneeded parts on their cars. If it’s there, you better figure out exactly why, before deciding you don’t need it.

Strategic Stupidity

I didn’t just suffer from procedural stupidity. I have engaged in some pretty major strategic stupidity. I wanted to design my own motorcycle engine. So when a neighbor machinist had an old obsolete Bostomatic mill, I jumped at the chance to buy it for $5,000. It was stupid to buy it when I could just send the parts out. I then decided to redesign the mill with a modern control system. Stupider still, I did a custom design with a PC motion-control card, instead of just paying to have a Fanuc control put on the machine. I ended up spending over $20,000, and eventually scrapped the machine since it didn’t have a tool changer and was slow and obsolete.

That taught to me to not spend time making things that I could just buy. If I wanted a milling machine to do prototype work, I could have bought a used machine for less than I spent on a project. It’s not even the money. Like that Teledyne revision fiasco, it was the time it took diddling with the machine, instead of designing the engine.

Short-Term Thinking Stupidity

My job as an analog engineer has cured me of some stupidity. I’m now wary of all “digital thinking,” when people say they are right and everyone else is wrong. I used to be that person, and now I see it as extremist. It’s one thing using extremes to analyze— cutoff, saturation, limit switches, etc., but don’t think that extremes make sense in the real world. Reality is not ones and zeros. I like the movie Charlie Wilson’s War. Gust Avrakotos, the character played by Philip Seymour Hoffman, has a great observation: Things that may seem like a good thing today, turn out to be bad tomorrow, and then might be good again after that. And then that good thing turns out to be bad, and on and on.

I liked that observation because it put a time dimension on our evaluation of outcomes. My stupidity was accepting concepts like “the greatest good for the greatest number” without realizing it all depends on how you define “good,” “greatest,” and “number”—not just momentarily, but over the course of time. You see this lack of a time dimension in the short-term thinking of some finance types. All they care about is getting that sale or this quarter’s results. They undermine the brand of the company by selling junk to pump up this month’s stock price. Instead of thinking only about sales, their primary concern should be marketing, and the brand their company projects.

I participated in this time dimension stupidity in my economics class in college. General Motors Institute wanted us all to end up in management. So, the economics class gave examples of how to manage a convenience store. They explained that you should divide the revenue from any given item by the floor space it takes up. Then just keep the most profitable items. It was an analysis designed by finance idiots. It was not just short-term thinking, it was simplistic, nearly infantile, thinking.

A modern convenience store is carefully designed to give a good customer experience crossed with exposing the customer with opportunities to buy (Fig. 3). The beer and soda are in the back, so you have to walk past the shelves full of tempting items to get there. The cashier areas have impulse buys like beef jerky and snacks.

3. There’s a real science to the layout of a convenience store. It’s not as simple as just keeping the fast-moving high-profit items. (Courtesy of Wikimedia)

It’s not dollars per square foot that determines if an item is on the shelf, it’s how it participates in the customer experience. Those old GMI professors were playing retail arithmetic instead of retail calculus. They would never put in fee-free ATMs like at WaWa. As a tech type, I bought into GMI’s finance stupidity for a very long time.

Grumbling Stupidity

One of my biggest stupidities was thinking others were stupid. I am ashamed to admit that as a young guy, I was one of those grumblers complaining about the management when I worked at Ford. Sure, back then, all of the auto business management had room for improvement. Thing is, when there were opportunities for me to manage things, I declined, preferring to be a worker bee. I see that now as shameful.

Don’t complain about management until you have walked in their shoes. If you can demonstrate conclusively that you can do better, most of the time, and in the long term, well then maybe you can toss stones at others. My dad told me to not be a grumbler and I did not listen or even ask why he said that. The older I get, the smarter my parents become.

Safety Stupid

I used to be stupid about safety. As a teen-aged co-op student at GMC Truck and Coach in Pontiac, Michigan, I worked on the charging systems of city buses. I was using a test rig that had a carbon-pile load for alternator testing. I had to drill out the terminal on a short 0000-gauge cable so that it would fit the bolt on the carbon pile. The drill press was a few steps away. I put in the 3/8-inch drill bit and held the cable on the work table. As I moved the drill into the soft copper terminal, it dug in, ripping the cable from my hand. The drill press then kept slamming the cable against the drill press post as the whole mess rotated. At least I was smart enough to use a slow speed.

The cable slapping made a horrific noise that you could hear all through the experimental garage. I was paralyzed with fear, but unhurt. An old tech ran up, judged the rotation of the cable, dashed in, turned off the drill, and dashed out, without getting hit by the flailing cable. I still remember this like it was yesterday. He was not angry, but very intense. He held his pinky finger with his other hand right before my nose. His pinky was missing the tip, maybe ¼ of an inch was cut off. “See that,” he barked. “I miss that every day. Clamp your work.” He went back to his job and I went back to mine, a little bit smarter.

I was fortunate that my very first co-op assignment at GMC Truck was in the Safety Department. It was a large factory, with a stamping plant, machine shop, and hydraulic riveters. To “freak out” the young kid, the employees in the safety group told me to look through the file cabinets full of pictures of accidents in the plant. One was a drill press with a thumb hanging down from the chuck, the tendons and ligaments wrapped around the drill bit. At 17, I was horrified.

I asked about it and the guys told me, “That is why you never wear gloves around rotating machinery. The chuck had a square-head set-screw for the drill bit. The operator was in a hurry and went to slow down the chuck so he could change the drill bit. Without gloves he would have gotten a nasty laceration. But with gloves, the cloth dug in and ripped his thumb off.” After that I made sure I tucked my tie into my shirt at the first button, the way I saw them do it. I don’t wear gloves around drills and such.

Heck, it's been a lifetime of stupid. I was in eighth-grade shop class. I was not wearing safety glasses. Across the room, two of my idiot friends were amusing themselves trying to cut a rat-tail file in the bar shear. I was looking at these antics without noticing the shear was aiming the file tip toward me. It took both of them hanging off the handle, but the file did finally shear. The piece they cut off whizzed by head like a bullet, a few inches from my eye.

I have now discovered 3M Nuvo safety glasses (Fig. 4). They have reading glass lenses, like a bifocal. I can read and see details when I want to, and I don’t need goofy goggles that go over my regular reading glasses. I bought three pairs and keep them in the garage, the house, the workshop, and my lab bench. I use them at night on my motorcycle.

4. Nuvo safety glasses from 3M are also reading glasses. These are missing the rubber nose bridge from all the use they get at my house.

I never wore gloves when I worked on my Harley. You can get parts solvent like Safety-Kleen on your hands and it’s not too bad. Then I stuck my hands into a 5-gallon bucket of Berryman’s Chem-Dip carburetor cleaner. My arms tingled for hours. My cuticles dried up and cracked for a week. I am surprised tumors did not appear. Now when I use Chem-Dip, I not only wear gloves, but a pair of great elbow-high gloves I found on Amazon.

Macho Stupidity

There are plenty of other stupidities amongst the large and small ones. There is gym stupidity, a version of macho stupidity. I thought the idea was to lift the most weight. I was blessed with a Harley buddy who was a personal trainer. He said that type of thinking just ends up getting you hurt. He then had me slowly lift an empty bar until I was completely exhausted. Now I do high reps with low weights so that I don’t tear a tendon, pull a muscle, or damage my joints. He also taught me good form with slow and controlled motion.

Like a lot of young guys, I had plenty of that tough-guy macho stupidity. I was on a motorcycle run when one of the new guys wiped out and broke his leg pulling into the bar. Too busted up to walk inside, they propped him up against a tree in the parking lot. The old-timers kept asking him if he wanted to go to the emergency room. The kid, tough like all us young morons, kept declining, playing macho act, especially in front of the gals. Soon the gals were bringing him beers and I saw him washing down pills with them, most likely barbiturates back then. Yeah, he was tough, stupid tough. Pretty soon the old-timers ruled that all beer and drugs be cut off for the new guy. After a couple hours, he was begging to go to the hospital. The Sergeant at Arms himself promptly obliged, taking the chase pickup truck.

We all come into this life ignorant. That’s fine, we are born a tabula rasa, a blank slate. To stay ignorant is stupid. I am so fortunate that I was exposed to people that gave me not only knowledge, but wisdom, so I can be a little less stupid as the years go on. The least stupid thing I can advise is to seek out wise and experienced people, like my pal Bob Pease, so you can embark on a program of continuous improvement.