Berlin researchers have developed tests for the mechanisms involved in decision-making that could shed light on the question of free will. The background of their research extends back to the 1970s, when the American researcher Benjamin Libet and others began studying the nature of cerebral processes during conscious decision-making. Lubet’s experiments are detailed in the 1991 book The User Illusion by Tor Norretranders. The upshot is that conscious behavior (in this case, to move a finger) is preceded by unconscious electrical activity—a readiness potential—in the brain. The readiness potential builds from a half second to a second before the act; the conscious decision to perform the act occurs about 20 ms before the act. The result suggests a deterministic brain in which free will is an illusion.

Now, in conjunction with Prof. Dr. Benjamin Blankertz and Matthias Schultze-Kraft from Technische Universität Berlin, a team of researchers from Charité’s Bernstein Center for Computational Neuroscience, led by Prof. Dr. John-Dylan Haynes, has taken a fresh look at this issue. The researchers tested whether people are able to stop planned movements once the readiness potential for a movement has been triggered.

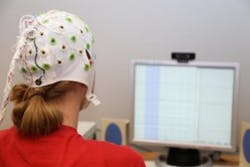

“The aim of our research was to find out whether the presence of early brain waves means that further decision-making is automatic and not under conscious control, or whether the person can still cancel the decision—i.e., use a ‘veto’,” explained Prof. Haynes. As part of this study, researchers asked study participants to enter into a “duel” with a computer, and then monitored their brainwaves throughout the duration of the game using electroencephalography. A computer was then tasked with using these EEG data to predict when a subject would move, the aim being to out-maneuver the player.

If the subjects acted deterministically—readiness potential, conscious decision, action—then the computer should always be able to predict the subject’s action. But subjects able to evade being predicted based on their own brain processes would be evidence that control over their actions can be retained for much longer than previously thought, which is exactly what the researchers were able to demonstrate.

“A person’s decisions are not at the mercy of unconscious and early brain waves. They are able to actively intervene in the decision-making process and interrupt a movement,” said Prof. Haynes. “Previously people have used the preparatory brain signals to argue against free will. Our study now shows that the freedom is much less limited than previously thought. However, there is a ‘point of no return’ in the decision-making process, after which cancellation of movement is no longer possible.”

The researchers plan further studies to investigate more complex decision-making processes.

About the Author

Rick Nelson

Contributing Editor

Rick is currently Contributing Technical Editor. He was Executive Editor for EE in 2011-2018. Previously he served on several publications, including EDN and Vision Systems Design, and has received awards for signed editorials from the American Society of Business Publication Editors. He began as a design engineer at General Electric and Litton Industries and earned a BSEE degree from Penn State.