“Ideal” Diode Controller Tackles Active Rectification, Protects Automotive Rails

The word “ideal” is often used in introductory engineering classes as a starting point to describe a component. However, at some point in any actual project or design, reality sets in, as there’s no ideal op amp, diode, battery, or resistor, to call out a few examples. The real question is: “How close is it to ideal, and in what ways is it not?” After all, a real diode has a forward voltage drop (VF) between 0.6 to 0.8 V (and about half that for Schottky diodes), while an ideal diode has a drop of zero volts—along with temperature-related shifts as well.

That’s why it’s impressive to see how close to ideal IC designers have been able to achieve via clever design techniques and architectures, as in the case of the “ideal” diode. Though not the first ideal-diode controller, the Texas Instruments LM74720-Q1 and similar LM74721-Q1 provide high-performance active-diode control over a pair of external n-channel MOSFETs via a dual gate-drive topology. One of these MOSFETs is controlled to emulate an ideal diode while the other MOSFET is for power-path on/off control, inrush-current limiting, and overvoltage protection.

The LM74720-Q1 is a 3- to 65-V ideal-diode controller with 27-µA IQ (on)/<3-µA IQ (off) for active rectification and load-dump protection. The similar LM74721-Q1 includes an integrated VDS clamp feature that enables system designs to forgo a transient-voltage-suppression (TVS) diode for pulse suppression per automotive-standard ISO7637.

Why do you need an ideal rectifier in an automotive scenario? In vehicles powered by an internal combustion engine (ICE), an alternator provides power to the electrical system by charging the battery during normal runtime. This rectified alternator output voltage can contain an ac voltage ripple superimposed on the dc battery voltage and varies with engine speed, regulator duty cycle, and load variations.

The rectifier isn’t just for ICE vehicles, either: In fully electric or hybrid systems (EV/HEV), the entire electrical load goes through dc-dc converters where, in the absence of a power-supply line choke, the output voltage of the dc-dc converter can inject an ac voltage ripple superimposed on the dc output voltage.

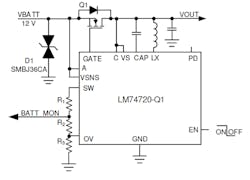

In a basic configuration of the LM74720-Q1, the voltage drop across the MOSFET is continuously monitored between the A and C pins, and the GATE to A voltage is adjusted as needed to regulate the forward voltage drop at 17 mV (typical) (Fig. 1).

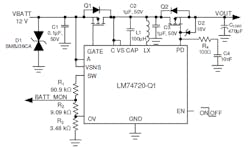

An enhanced configuration adds reverse-battery protection, overvoltage protection, and inrush-current limiting (Fig. 2).

Housed in 12-lead, 3- × 3-mm WSON packages and priced at under $1 (1,000 pieces), these automotive-focused ICs meet stringent AEC-Q100 requirements, of course, as well as the other automotive-related mandates for protection and voltage surges (and there are many). in addition to the 30-page LM74720-Q1 and 27-page LM74721-Q1 datasheets, there’s also the LM7472EVM evaluation board and its comprehensive 25-page User’s Guide for further hands-on exploration (Fig. 3).

For those not familiar with the need for active rectification or its implementation, Texas Instruments also has an informative four-page application brief “Active Rectification and its Advantages in Automotive ECU Designs.”

About the Author

Bill Schweber

Contributing Editor

Bill Schweber is an electronics engineer who has written three textbooks on electronic communications systems, as well as hundreds of technical articles, opinion columns, and product features. In past roles, he worked as a technical website manager for multiple topic-specific sites for EE Times, as well as both the Executive Editor and Analog Editor at EDN.

At Analog Devices Inc., Bill was in marketing communications (public relations). As a result, he has been on both sides of the technical PR function, presenting company products, stories, and messages to the media and also as the recipient of these.

Prior to the MarCom role at Analog, Bill was associate editor of their respected technical journal and worked in their product marketing and applications engineering groups. Before those roles, he was at Instron Corp., doing hands-on analog- and power-circuit design and systems integration for materials-testing machine controls.

Bill has an MSEE (Univ. of Mass) and BSEE (Columbia Univ.), is a Registered Professional Engineer, and holds an Advanced Class amateur radio license. He has also planned, written, and presented online courses on a variety of engineering topics, including MOSFET basics, ADC selection, and driving LEDs.