An MIT team led by Professor Neil Gershenfeld has applied the “facts of life” to motors. Living things are built out of near-infinite combinations of just 20 amino acids, so would it be possible to create a kit of just 20 fundamental parts that could be used to assemble multiple mechanical constructs (perhaps a more-tangible comparison would be the use of well-known LEGO parts)?

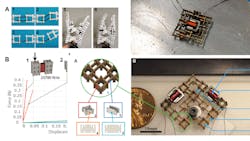

The answer to Prof. Gershenfeld’s question is “maybe.” Their latest demonstration of the possible validity of the idea is a seen in a set of five tiny fundamental parts that can be assembled into a wide variety of functional devices, including a tiny “walking” motor that can move back and forth across a surface or turn the gears of a machine (Fig. 1).

They used a group of five millimeter-scale components, all of which can be attached to each other by a standard connector. The goal is to have a kit of parts that could be used to assemble different robots as needed, and even disassembled and reassembled into other configurations with strengths and sizes. For control, the team used parts with millimeter-sized integrated circuits, as well as parts with electrical connections in three dimensions.

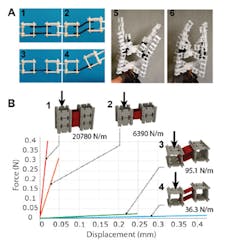

These parts include rigid and flexible components (based on earlier published work), plus electromagnetic parts, a coil, and a magnet. They were assembled into a motor arrangement that moves in discrete mechanical steps, which in turn can be used rotate a geared wheel, see video here.

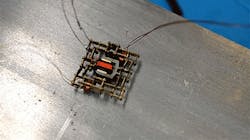

Their mobile motor—named Discretely Assembled Walking Motor (DAWM)—turns those steps into locomotion, so it can walk along a surface (Fig. 2) and video here.

Motion is energized via voice-coil actuator components that produce up to 42 mN of force with strokes of 2 mm. With stepping at rates of up to 35 Hz, the resultant velocity can be as high as 25 mm/s. Multiple DAWM systems can be linked to increase force, and they can be driven in-phase or out-of-phase to produce intermittent or continuous force, respectively.

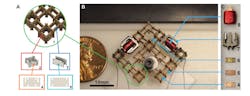

The parts are 3.53 mm in their longest dimension and 254 μm thick; their smallest feature size is 200 μm. By embedding degrees of freedom in the parts themselves, the team was able to assemble mechanisms and linkages.

The flexural parts were fabricated using a multi-layer laminate technique that they called PC-MEMS (printed-circuit MEMS) or SCM (smart-composite microstructures); they’re made from layers of brass (100 μm thick) and Kapton (25 μm thick), joined with two layers of B-staged Pyralux adhesive (12.5 μm thick). The resultant parts have a hinge joint that’s much more compliant about its rotation axis than it’s off-axis—very desirable attributes for the basic hinged joint as well as a parallelogram linkage assembled from two degree-of-freedom struts (Fig. 3).

Handcrafting these mini-motors one at a time is feasible but not desirable. Instead, graduate student Will Langford developed a machine that’s somewhat of a hybrid between a 3D printer and a pick-and-place machine. It can produce complete robotic systems directly from digital designs (Fig. 4).

Here's a related video:

Prof. Gershenfeld says this machine is a first step toward to the project's ultimate goal of “making an assembler that can assemble itself out of the parts that it's assembling.”

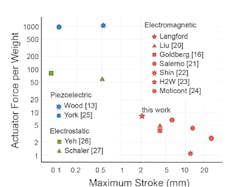

The team rounded out their analysis of their device’s performance with a graph comparing the stroke versus acceleration/weight of their design to other research and commercial millimeter-scale actuators, with reference citations (Fig. 5).

The mini-motor project details were presented at the International Conference on Manipulation, Automation and Robotics at Small Scales (MARSS) in Helsinki, Finland, where their paper “A Discretely Assembled Walking Motor” (by Gershenfeld and Langford) was selected as the conference's best student paper (note: the paper only mentions Langford’s assembly machine in brief).

About the Author

Bill Schweber

Contributing Editor

Bill Schweber is an electronics engineer who has written three textbooks on electronic communications systems, as well as hundreds of technical articles, opinion columns, and product features. In past roles, he worked as a technical website manager for multiple topic-specific sites for EE Times, as well as both the Executive Editor and Analog Editor at EDN.

At Analog Devices Inc., Bill was in marketing communications (public relations). As a result, he has been on both sides of the technical PR function, presenting company products, stories, and messages to the media and also as the recipient of these.

Prior to the MarCom role at Analog, Bill was associate editor of their respected technical journal and worked in their product marketing and applications engineering groups. Before those roles, he was at Instron Corp., doing hands-on analog- and power-circuit design and systems integration for materials-testing machine controls.

Bill has an MSEE (Univ. of Mass) and BSEE (Columbia Univ.), is a Registered Professional Engineer, and holds an Advanced Class amateur radio license. He has also planned, written, and presented online courses on a variety of engineering topics, including MOSFET basics, ADC selection, and driving LEDs.