Light Drives Micrometer-Sized Motor and Gear Train

What you'll learn:

- The challenges of fabricating micromotors and geartrains with comparable size to a human cell.

- The problems of powering such motors.

- How metasurfaces allow projected laser output to power these micromotors.

The history of scientific progress is often marked by applications that leverage technologies, materials, and processes developed and extended by unrelated applications. A clear example of this is how IC-related processes technologies lead to microelectromechanical-system (MEMS) devices.

Using these resources, a team at University of Gothenburg (Sweden) extended these processes and techniques to develop and evaluate a light-powered micromotor and gear train with gear diameters in the micrometer range. They maintain that this is a significant shrink compared to most existing designs that have “stalled out” at about 0.1-mm minimum diameter.

The Challenges of Mini Geared Machines

What’s a geared mechanical machine? It can be defined as at least two mechanical parts interacting with each other to form a cohesive unit capable of generating and transmitting work. The concept of such micromotors and mechanical systems isn’t new, of course, but incorporating them into functional microscopic, geared mechanisms remains a significant challenge.

Other traditional semiconductor manufacturing methods for electrostatically driven gears are restricted by the need for electric connectors, which occupy considerable space around each micromotor and limit both miniaturization and parallelization. While “far-field” approaches such as use of AC electric, magnetic, and non-coherent light fields allow further miniaturization of individual micromotors, these bring other performance issues.

Optical Metasurfaces, a Metarotor, and Lasers

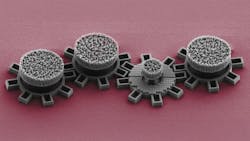

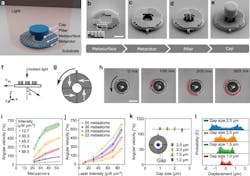

The team leveraged fabrication technology to develop geared mechanisms with optical metasurfaces that operate under uniform laser illumination. This micromotor core is a metarotor — a ring structure containing a metasurface — that’s securely anchored to a glass chip using a capped pillar (Fig. 1).

Using silicon as the primary material ensures compatibility with standard photolithography, facilitating large-scale manufacturing. This approach creates a versatile platform for precise control and movement of geared functional devices, enabling unprecedented capabilities in microscale and nanoscale mechanical systems.

In their research, the researchers show that microscopic machines can be driven by optical metamaterials — small, patterned structures that can capture and control light on a nanoscale. Using traditional lithography, gears with an optical metamaterial are manufactured with silicon directly on a microchip, with the gear having a diameter of a few tens of micrometers (the human hair often cited for comparison average is 70 µm, but ranges from 20 to 180 µm).

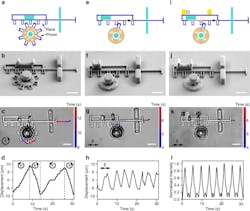

By shining a laser on the metamaterial, the researchers can make the gear wheel spin and even drive and control a gear train (Fig. 2).

The intensity of the laser light controls the speed. It’s also possible to change the direction of the gear wheel by changing the polarization of the light. Furthermore, the gears can be part of an arrangement that converts rotation into linear motion (Fig. 3), perform periodic movements, and control microscopic mirrors to deflect light.

Delving into Durability

The researchers also investigated the legitimate but easy-to-ignore issue of motor durability. Although the chip isn’t yet optimally packaged for long-term stability, the motor remains operational under continuous illumination for up to 11 hours. Furthermore, it doesn’t undergo structural degradation even when irradiated for 11 hours and stored for up to six months

Nevertheless, while the motor is in a steady-state drive mode, its rotational speed gradually decreases and eventually the motor stops. This is likely due to changes in the solution environment (such as local surfactant redistribution and the accumulation of impurities), leading to increased friction at the motor-substrate interface.

However, the motor can resume rotation after gentle cleaning and solution exchange. This indicates that these effects are reversible rather than corrosive, and can be mitigated through improved packaging and fluid handling.

The fascinating work is described in their readable paper published in Nature Communications, “Microscopic geared metamachines” (one of the shortest titles I have seen in an academic paper). The associated lengthy Supplementary information section adds further project fabrication, analysis, test, and possible application details; a table and detailed discussion comparing existing alternatives; and — as you would expect, given the nature of the project — over a dozen videos.

About the Author

Bill Schweber

Contributing Editor

Bill Schweber is an electronics engineer who has written three textbooks on electronic communications systems, as well as hundreds of technical articles, opinion columns, and product features. In past roles, he worked as a technical website manager for multiple topic-specific sites for EE Times, as well as both the Executive Editor and Analog Editor at EDN.

At Analog Devices Inc., Bill was in marketing communications (public relations). As a result, he has been on both sides of the technical PR function, presenting company products, stories, and messages to the media and also as the recipient of these.

Prior to the MarCom role at Analog, Bill was associate editor of their respected technical journal and worked in their product marketing and applications engineering groups. Before those roles, he was at Instron Corp., doing hands-on analog- and power-circuit design and systems integration for materials-testing machine controls.

Bill has an MSEE (Univ. of Mass) and BSEE (Columbia Univ.), is a Registered Professional Engineer, and holds an Advanced Class amateur radio license. He has also planned, written, and presented online courses on a variety of engineering topics, including MOSFET basics, ADC selection, and driving LEDs.