Skin Patches Crafted for Wound Monitors, Light-Printable Electrodes

What you'll learn:

- Why skin-based sensing of critical medical parameters is an attractive approach.

- How an innovative wound patch provides on-skin monitoring of critical healing factors.

- How a unique polymerization material allows for creation of skin electrodes using only visible light.

Sensing of human medical parameters via the skin is an attractive option for obvious reasons: it’s non-invasive, relatively easy to get test subjects, has few regulatory issues, and is easy to observe. For these and other reasons, this approach to test and measurement instrumentation is receiving a lot of research attention, ranging from complete subsystems down to basic “probes” (electrodes).

Two recent examples of these extremes are an in-place wound-monitoring patch and light-printable electrodes.

Wound-Monitoring Patch

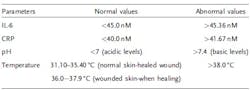

A team at RMIT University (Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology/Australia) has developed a skin patch that monitors wound healing remotely via a Bluetooth connection (Fig. 1). The proof-of-concept device is designed for reuse, making it more cost-effective and practical than disposable smart bandages and other emerging wound-monitoring technologies.

The device uses advanced integrated sensor technology to monitor inflammation, pH, and temperature sensors and continuously track key healing indicators. It embeds flexible sensors based on high-resistivity silicon-based sensor technology that can be placed on or next to a wound under the dressings.

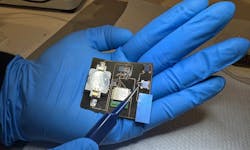

A triangulated approach of measuring CRP, IL-6 proteins, pH, and temperature is used to wirelessly track changes in parameters that indicate the progress (or lack thereof) of wound healing. High temperatures signal inflammation or infection, while changes in pH levels can indicate different stages of wound healing (Fig. 2). There’s only a slight difference between normal and abnormal values.

[Note: CRP is C-reactive protein, a substance made by the liver that indicates inflammation in the body, rising significantly with acute infections, injuries, or chronic inflammatory diseases; IL-6 (Interleukin-6) is a versatile cytokine protein that acts as a crucial signaling molecule in immunity, inflammation, tissue repair, and metabolism, initiating alarm signals for infections or injury.]

A SoC-based platform was developed to accommodate a combination of the CRP and IL-6 biosensors, pH sensor, and temperature sensor, all mounted onto a flexible cutaneous wearable patch. This was integrated with Bluetooth wireless communication capabilities (Fig. 3) and placed in situ on the wound site, sandwiched between the wound gauze and the dressing.

Their work is described in detail in the paper “Multiplexed cutaneous wound monitor for point-of-care applications” published in Advanced NanoBiomed Research. The paper includes medical background plus a detailed description of the concept, medical issues, sensor implementation, circuitry, and test results.

Light-Printed Skin Electrode

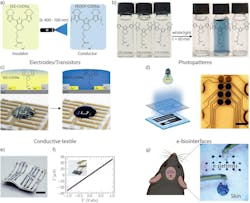

Researchers at Linköping University and Lund University in Sweden have demonstrated how visible light can be used to form electrodes made from conductive plastics, and it does so without relying on hazardous chemicals. The method allows electrodes to be produced on many different surfaces, including skin, possibly easing the way new types of electronics and medical sensors.

They used conductive plastics, also called conjugated polymers, that combine the electrical behavior of metals and semiconductors with the flexibility and softness of plastics, making them especially useful for applications that require both conductivity and adaptability.

Traditionally, polymerization — creation of long chains of hydrocarbons from units know as monomers — requires strong and sometimes toxic chemicals. This limits how easily the process can be scaled up and restricts its use in sensitive fields such as medicine.

The researchers developed a way for polymerization to occur using only visible light. The key lies in specially designed water-soluble monomers created by the research team. The process doesn’t require toxic chemicals, harmful UV light, or additional treatment steps to produce functional electrodes.

In practice, a liquid solution containing the monomers is applied to a surface, and a laser or another strong light source is used to draw detailed electrode patterns directly onto that surface. Any solution that doesn’t polymerize can be washed away, leaving only the finished electrodes behind (Fig. 4).

The electrical properties of the material are critical. As the material can transport both electrons and ions, it can communicate with the body in a natural way, while its gentle chemistry ensures that tissue tolerates it.

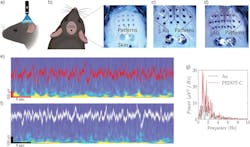

To test the approach, the researchers used light to pattern electrodes directly onto the skin of anaesthetized mice. Compared with conventional metal EEG electrodes, the new electrodes showed clearer recordings of low-frequency brain activity (Fig. 5).

Their work is available as “Visible-Light-Driven Aqueous Polymerization Enables in Situ Formation of Biocompatible, High-Performance Organic Mixed Conductors for Bioelectronics” published in Angewandte Chemie (German Chemical Society). Much of the paper is about the chemistry of the polymers and process, but there’s also some discussion and analysis of electronic aspects.

About the Author

Bill Schweber

Contributing Editor

Bill Schweber is an electronics engineer who has written three textbooks on electronic communications systems, as well as hundreds of technical articles, opinion columns, and product features. In past roles, he worked as a technical website manager for multiple topic-specific sites for EE Times, as well as both the Executive Editor and Analog Editor at EDN.

At Analog Devices Inc., Bill was in marketing communications (public relations). As a result, he has been on both sides of the technical PR function, presenting company products, stories, and messages to the media and also as the recipient of these.

Prior to the MarCom role at Analog, Bill was associate editor of their respected technical journal and worked in their product marketing and applications engineering groups. Before those roles, he was at Instron Corp., doing hands-on analog- and power-circuit design and systems integration for materials-testing machine controls.

Bill has an MSEE (Univ. of Mass) and BSEE (Columbia Univ.), is a Registered Professional Engineer, and holds an Advanced Class amateur radio license. He has also planned, written, and presented online courses on a variety of engineering topics, including MOSFET basics, ADC selection, and driving LEDs.