New Bluefield DPUs Drill Deeper into the Data Center

>> Top Stories of the Week

.. >> GTC 2021 digital issue

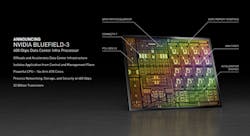

NVIDIA is stepping up its challenge in part of the data center market dominated by Broadcom, Intel, Xilinx, and others with its new generation of data processing units, or DPUs, for servers.

Last year, the Santa Clara, California-based company rolled out the first in its family of Bluefield DPUs that can offload software-defined networking, storage, and security workloads that have become a huge drag on the central processing units (CPUs) in servers. On Monday, it revealed its latest generation of chips, Bluefield-3, to take over even more of these infrastructure chores.

Bluefield-3 is designed to be used by cloud vendors and others who run colossal data centers. "Modern hyperscale clouds are driving a fundamental new architecture for data centers," said CEO Jensen Huang said in a statement. "A novel type of processor, designed to process data center infrastructure software is needed to offload and accelerate the tremendous compute load of virtualization, networking, storage, security and other cloud-native AI services."

A DPU is a type of server networking card—also called a SmartNIC—that is increasingly used in data centers to handle more of the behind-the-scenes data-management workloads that are choking CPUs. NVIDIA's Bluefield family of DPUs is one of the pillars of its strategy in the data-center business, where it is the dominant player in graphics processing chips (GPUs) for AI.

The Bluefield-3 was announced at NVIDIA's annual GPU Technology Conference (GTC), where it also revealed its entry into the data-center processor market with its Arm-based Grace CPU. The DPU incorporates networking silicon from NVIDIA's Mellanox Technologies deal and CPU cores based on Arm's core designs. NVIDIA agreed to buy Arm for around $40 billion last year.

For years, most of the data management and other infrastructure chores in the data center ran on generic network interface cards, or NICs, and separate bundles of hardware that are attached to servers or storage to connect them to Ethernet networks. But more and more of the chores have been replaced in recent years by software relegated to the CPU in the server.

One of the disadvantages is that the infrastructure software in the server strains the CPU. By offloading these functions to a DPU or SmartNIC, the CPU in the server can focus on other workloads. Data management chores—from ferrying data between the servers to storing and securing it—drain up to 30% of the CPU resources in modern data centers, NVIDIA estimates.

NVIDIA said Bluefield DPUs have enough compute and memory for more of the infrastructure software and behind-the-scenes management services in the data center to be loaded into it.

At the heart of the Bluefield DPU is a programmable networking chip with 16 Arm Cortex-A78 cores, upgrading from the eight CPU cores based on Arm's Cortex-A76 technology in the previous generation, the Bluefield-2 DPU. The cores have access to 8 MB of secondary L2 cache and 16 MB of LLC cache. NVIDIA said the DPU is supplemented by 16 GB of onboard DDR5 DRAM, doubling the speed from the DDR4 memory in the Bluefield-2.

There is also a data-path accelerator with 16 cores and 256 threads and a wide range of other accelerators that can offload networking, storage, and security workloads from the host CPU. NVIDIA said that it also incorporates Mellanox's ConnectX networking interface that supports 400-Gb/s Ethernet or Infiniband, up from the 200-Gb/s links in the previous-generation DPU. The chip also has a 1 Gb/s Ethernet out-of-band management port.

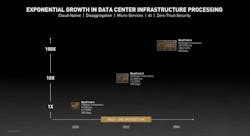

The improvements in the Bluefield-3 DPU add up to 10 times more computing power than the Bluefield-2. NVIDIA said the latest DPU has enough performance to run data-management and other infrastructure software that would engage up to 300 CPU cores. The resources saved in the process can then be used by other applications and services running on the server's CPU.

Under the hood are roughly 22 billion transistors that translate into 1.5 trillion operations per second (TOPS) of performance, up from less than a billion transistors packed in its previous generation of chips. Nvidia said the DPU harnesses the added computing power to process, secure, and store more data in real time—also called the "line-rate"—as it travels from server to server.

The SmartNICs, which can run operating systems such as Linux and VMWare, also integrate real-time clocks in hardware that lend themselves to the timing requirements of 5G networks.

The chips are slapped on server networking cards that have 32 PCIe Gen 5 lanes for the first time in the product category, doubling the data speeds of the PCIe Gen 4 interconnects in the previous generation. The chips at the heart of the Bluefield DPUs also have a DDR5 memory interface to connect to additional sticks of DRAM. It is unclear what technology node it uses.

These types of networking chips have become a huge battleground in data centers in recent years, with industry giants such as Intel, Broadcom, Xilinx, and others fighting for design wins.

Intel—the world's largest maker of central processing chips in data centers—and Broadcom—the global leader in standard Ethernet networking cards for servers—are wrestling to win more market share in the category. Xilinx has also rolled out smart networking cards based on chips that incorporate Xilinx FPGAs and Arm CPUs, fully programmable with its Vitis software tools.

Fungible, which was started by one of the founders of Juniper Networks and has amassed more than $300 million in funding, and networking startups Netronome and Pensando are also targeting the category. Public cloud service vendors Amazon and Microsoft are investing more in internally designed chips for their data centers, including proprietary SmartNICs.

NVIDIA is trying to differentiate itself by integrating its Bluefield DPUs with GPUs to bring more AI to the network. It could also leap ahead of rivals by leveraging its vast developer ecosystem.

NVIDIA said that it was on pace to introduce another new generation of the DPU, Bluefield-4, in 2024 with the GPU and CPU integrated on the same die, delivering up to 1,000 TOPS of overall performance and 800-Gb/s networking over Ethernet. According to the company, the chip at the heart of the DPU would have 64 billion transistors and use the on-die GPU to provide AI acceleration.

Huang said NVIDIA's strategy is to introduce a new generation of its server networking cards every year-and-a-half with an order of magnitude more performance with every new product.

It is also trying to stand out in the category by giving customers more tools to boost security. The Bluefield-3, which will run cryptography up to four times faster, can offload and isolate the running of security agents from host CPUs. By isolating them from the CPU, NVIDIA said the DPU can prevent viruses or attackers from spreading throughout the data center in the event the server is compromised.

NVIDIA noted that the DPUs also can handle AI-based functions such as security, network, and video analytics. Other security features include secure boot and management of cryptographic keys.

NVIDIA rolled out on Monday its Morpheus technology, a set of software tools that allow companies to identify viruses and other threats faster by examining more of the data traveling throughout the network. Morpheus uses the additional computing power in the Bluefield-3 to run machine learning that can survey every single data packet on the network, then identify and block attacks.

Cybersecurity tools on the market today usually work by scanning the data traversing a company’s network for anomalies. But many of these tools tend to analyze only a small amount of information before using it to train a machine learning model. NVIDIA estimates that today these tools examine only 5% of the data in the network, giving the models an incomplete sense of the threats.

NVIDIA said the Bluefield DPU acts as what it calls a “monitoring agent" for its Morpheus software, allowing companies to analyze every packet traversing the network in real time and spot more trouble. Morpheus also includes pre-trained models to pinpoint viruses, leaked credentials, secret keys smuggled by hackers around the network, and other vulnerabilities.

By adding features to safeguard massive data centers, the Morpheus technology could convince more of customers in the cybersecurity space to buy or support Bluefield DPUs.

It also rolled out its first set of programming tools and other software, DOCA, to complement the Bluefield DPU. The software stack lowers the bar for customers to build software-defined, hardware-accelerated applications and services running on the DPU. NVIDIA said that DOCA is analogous to CUDA, the toolset it developed to get more performance out of its GPUs.

The software suite includes a runtime environment to create, compile, and improve workloads running on Bluefield DPUs, as well as orchestration tools that can be used to provision, update, and oversee thousands of the DPUs in the data center. The tools also feature libraries, APIs, and other pre-packaged applications to be used in packet inspection or load balancing.

NVIDIA said the BlueField-3 DPU would be available to potential customers in the first quarter of 2022 and that it is currently supplying its Bluefield-2 DPU to server OEMs and cloud players.

Major server manufacturers, including Lenovo, Dell Technologies, Supermicro, and others, are integrating Bluefield DPUs into new systems. NVIDIA said the server chips are also supported by cloud data-center software suppliers Canonical, Red Hat, and VMware; cybersecurity firms Guardicore and Fortinet; and edge software vendors from Cloudflare to Juniper Networks.

About the Author

James Morra

Senior Editor

James Morra is the senior editor for Electronic Design, covering the semiconductor industry and new technology trends, with a focus on power electronics and power management. He also reports on the business behind electrical engineering, including the electronics supply chain. He joined Electronic Design in 2015 and is based in Chicago, Illinois.