New Touch-Sensing Tech Leads to Larger, Thinner, and Foldable Displays

What you'll learn:

- Why thinner OLED stackups are more susceptible to EMI and noise, and the impacts for touch sensing.

- How multi-frequency-region parallel sensing (MFRPS) improves touch accuracy, scalability, and latency.

- How MFRPS can apply to applications in consumer electronics, automotive, retail, and industrial devices.

- How MFRPS is supplemented by innovations such as continuous sinewave sensing, pseudo-sine drive, and parallel IQ demodulation.

As demand for larger, thinner, and more responsive touchscreens intensifies, so does the complexity of engineering them. Designers of smartphones, tablets, automotive displays, and industrial control interfaces face a paradox: Users expect increasingly sophisticated touch performance — even in harsh electromagnetic environments — while mechanical designs push the physical limits of thinness and integration.

Those pressures are intensifying with the rise of thinner, larger panels in the latest wave of foldable devices. The category is expanding fast: The foldable-display market is projected to surge from $8.9 billion in 2025 to $76.1 billion by 2035, growing at a 24% average annual rate over the decade, according to Future Market Insights. More advanced OLED screens built on low-temperature polycrystalline-oxide (LTPO) backplanes are also trending up, with a projected compound annual growth rate of 14.5%.

This surge is largely driven by consumer demand for brighter displays and extended battery life, which in turn is pushing display assemblies to become thinner and more power-efficient. However, this move toward thinner stackups introduces several challenges related to noise interference and signal degradation that engineers must overcome to maintain high touch responsiveness and accuracy.

One of the key friction points in this evolution is the signal integrity of capacitive touch systems. As display assemblies shrink and stack vertically, touch sensors are often placed closer to sources of electromagnetic interference (EMI), including display drivers and power circuitry. The result is a degraded signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) that undermines the responsiveness and accuracy of touch input.

To address this, a new approach to capacitive sensing is emerging: multi-frequency-region parallel sensing (MFRPS). This architectural shift offers engineers a path forward to solve noise immunity, scalability, latency, and power efficiency challenges across a wide spectrum of use cases.

Why Traditional Touch Sensing is Struggling with Thinner Displays

The current standard in capacitive touch sensing is single-frequency scanning, where driving bursts or steps equals the number of transmitters. While effective for small displays in less demanding environments, this method starts to falter in the context of next-generation touch displays.

>>Download the PDF of this article, and check out the TechXchange for similar articles and videos

Capacitive touch systems in thinner displays are especially vulnerable to three categories of noise:

- Touch-to-display (T2D) noise: Arises from the sharp rising and falling edges of traditional square-wave driving signals, which introduce harmonic interference into the display, resulting in flicker or visual distortion.

- Display-to-touch (D2T) noise: Stems from high-frequency switching activities in the display during refresh cycles, which couple back into the touch sensors and cause phantom touches or signal corruption.

- Settling noise: Results from increased RC time constants in thinner stackups, which prevent capacitive elements from fully charging. This reduces the effective SNR and compromises touch accuracy.

Navigating all of these potential noise sources is becoming more challenging. Foldable and large displays, featuring thinner stackups and expansive panel areas, add to the challenges presented by EMI. At the same time, multitouch gestures require very low latency and precise position tracking of position. Active pens, which use electronics to allow users to write directly onto the display, require the same things. In battery-powered devices, touch controllers must stay alert in always-on modes without draining power budgets.

But the reality is that single-frequency scanning, with its inherently longer cycle times and susceptibility to interference, has reached a performance ceiling.

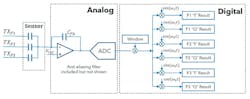

MFRPS enhances traditional single-frequency scanning by dividing the panel into several independently operated regions, each with a separate code-division-multiplexing (CDM) burst operating at a different frequency (Fig. 1). This not only reduces effective sensing bandwidth and susceptibility to noise, but it also enables more targeted filtering and enhanced noise immunity. By distributing the sensing workload and isolating frequency zones, engineers gain more flexibility and scalability across varying screen sizes and configurations.

MFRPS: Operating in Parallel at Different Frequencies

At its core, MFRPS reimagines how a capacitive touch panel is scanned to sense for touch. Instead of operating at a single frequency or sweeping through them one at a time, MFRPS divides the panel into several zones, each operating simultaneously but at different frequencies. These zones are scanned in parallel, enabling the system to collect more data in less time and with higher fidelity (Fig. 2).

This approach comes with several key advantages:

- Reduced panel scan time: By conducting simultaneous measurements across multiple regions, overall frame rates increase dramatically, resulting in less latency between touch and response.

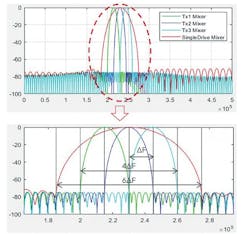

- Enhanced noise immunity: Frequency diversity allows the system to isolate and mitigate interference more effectively (Fig. 3).

The Innovations Between the Lines of Parallel Touch Sensing

MFRPS can’t solve all of the noise, power, and latency challenges of foldable and other advanced displays by itself. In most cases, it’s complemented by several other innovations embedded in the touch controller behind the display:

- Continuous-time digital sensing: Replacing traditional analog front ends (AFEs), continuous-time digital sensing uses high-speed sampling and real-time signal processing to further improve SNR. The dAFE inside the touch controller moves the mixers from analog domain to digital domain. Without the dAFE, each mixer would require dedicated analog circuits, totaling six mixers when using three I/Q pairs.

- Continuous-time digital sensing works with MFRPS to narrow the sensing bandwidth, filter out transient noise, and preserve signal integrity.

- Pseudo-sine wave drive: Traditional square-wave signals introduce harmonics that can interfere with the integrity of touch signals and the clarity of the display. The touch controller leverages pseudo-sine drive to replace sharp-edged square waves used to drive the display with smoother sine waves. As a result, it can significantly reduce harmonics, improving the display’s clarity when it’s being touched.

- The pseudo-sine wave drive technology also enables higher drive voltages on low-voltage processes.

- Parallel IQ demodulation: Active stylus input demands not only high resolution, but also reliable signal separation between the pen tip and auxiliary elements. MFRPS-based architectures support in-phase (I) and quadrature (Q) signal demodulation in parallel, increasing accuracy and minimizing jitter.

- Power-efficient doze modes: In mobile devices and embedded systems, touch sensing must remain responsive even during low-power states. Traditionally, “doze” modes require two bursts to scan the panel — a technique that doubles sensing time and power use. With MFRPS, a single burst can achieve the same result, reducing doze power consumption by up to 40%.

The Shift to Parallel Touch Sensing: What It Means for Engineers

MFRPS brings many technical benefits to the table. But its value lies in how it simplifies and strengthens the design process for a wide range of devices, enabling thinner and more complex displays, even in electrically hostile environments. MFPRS is also ideal for pen and gesture-heavy interfaces without draining battery life.

The versatility of MFRPS also makes it an enabler across multiple sectors, including:

- Consumer electronics

- Industrial applications

- Retail and point-of-sale systems

- Automotive

Besides its performance and flexibility, one of the most important facets of MFRPS is its ability to unify touch interface design under a single scalable architecture. From compact mobile devices to widescreen dashboards and rugged panels, engineers have more freedom to select how many frequency regions to use for different applications, giving them a common sensing framework.

A Foundation for the Future of Touch Sensing

MFRPS marks a major shift in the development of touch-controlled systems. It addresses long-standing limitations of standard capacitive sensing by increasing parallelism, introducing frequency diversity, and improving both power efficiency and scalability.

As displays grow more immersive and interactive, the touch technology that drives them must evolve, too. MFRPS is ready to meet that challenge — not as a niche enhancement, but as a foundational architectural shift that supports the next generation of human-machine interaction (HMI).

>>Download the PDF of this article, and check out the TechXchange for similar articles and videos

About the Author

Gordon Shen

Principal IC Architect, Synaptics Inc.

Gordon (Guozhong) Shen is Principal IC Architect at Synaptics, a position he has held since 2014. Prior to this role, Gordon served as a Senior Principal Member of Technical Staff at Maxim Integrated from August 2009 to February 2014, and before that, he worked as a Senior Hardware Engineer at Apple from February 2008 to August 2009. Gordon's career started at LDS Test and Measurement, where he was a Lead Hardware and DSP Engineer from January 2001 to February 2008. He holds a PhD degree from Zhejiang University.