Modernizing the AC Power Grid for Future Stability

Our electric grid—built roughly a century ago—was designed around large, centralized energy resources based on heavy rotating generators found in hydroelectric, nuclear, coal, and natural gas power plants (Fig. 1). These power plants are huge infrastructure projects that take 10-15 years to build and commission, so it’s a major effort to add any new facilities.

However, global electricity demand is increasing at approximately 4% annually. Two major drivers are pushing this demand:

- Electric vehicles, as transportation becomes increasingly electrified.

- Artificial intelligence, specifically the data centers required to support AI computing workloads.

By 2030, EV charging alone is expected to represent about 2% of global electricity demand. In parallel, AI-related data centers will add tens to hundreds of megawatts of additional load per site, significantly increasing strain on grid infrastructure.

Meeting these demands will challenge existing grid capacity and the already complex permitting process that’s required to bring new energy resources online. Doing so at the necessary pace will require substantial, coordinated investments in energy infrastructure.

It may be tempting to assume that we can close the energy demand gap by just adding more wind and solar capacity and electrifying all vehicles… and then calling the job. However, such a simple approach won’t work due to the architecture of the grid.

The Grid: A “Big Machine” in Balance

To understand why we can’t just throw renewables on the grid, let’s take a closer look at how the grid is designed. The grid must remain continuously balanced so that supply equals demand. This requirement exists because, in practical terms, the grid has almost no inherent energy storage.

While storage technologies are emerging, today the amount of true grid-scale storage is still negligible. As a result, supply must always match demand for the grid to remain stable, reliable, and economical.

>>Download the PDF of this article

In Europe, the grid frequency is 50 Hz; in other regions, such as North America, it’s 60 Hz. This frequency is determined by the physical rotational speed of generators powering the grid. Frequency stability is generally achieved by the rotating machines’ inertia, which resists changes in speed and helps to maintain stability in the face of supply/demand fluctuations.

Grid operators constantly monitor the frequency and use automated systems to make adjustments. They send signals to generators to either increase or decrease their output to match the real-time demand, keeping the frequency within a tight, stable range. This frequency is controlled within tight limits, typically within ±150 mHz in large networks.

Balance between supply and demand must be maintained. When supply matches demand, the frequency remains steady at these nominal values.

When demand or consumption exceeds supply or generation, the generators must work harder, causing them to slow down and decrease the frequency (Fig. 2). Conversely, when supply or generation exceeds demand or consumption, meaning a surplus of power, the generators' turbines speed up, increasing the frequency.

A similar principle applies to voltage. When demand outpaces supply, voltage drops; when supply exceeds demand, voltage rises. Although voltage fluctuations can be somewhat mitigated, since most electronic devices are designed to operate across a range of input voltages, these variations still impact grid performance with respect to voltage stability.

Adding Renewables to the Mix

The key challenge is that wind, solar, and electric vehicles are decentralized energy sources that produce variable output power, unlike traditional synchronous generators that deliver highly stable and consistent power. Today’s grid was not originally designed to accommodate large amounts of such distributed and variable assets.

The integration of variable renewable sources like solar and wind can theoretically lead to more frequency fluctuations, requiring modern control systems that are designed to manage these changes. Therefore, integrating these decentralized resources at scale will require deliberate, strategic planning and the development of a modernized grid architecture. Such an architecture would leverage smart-grid technologies to maintain stability, support bidirectional power flows, and ensure long-term reliability.

Architecting the Modern Grid

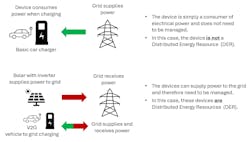

The key concept to introduce here is the distributed energy resource (DER). A DER is the fundamental building block of the evolving grid architecture commonly referred to as the smart grid.

A DER is typically a DC-AC converter—often called an inverter—that uses power electronics for energy conversion as compared to rotating machines. Importantly, it can be remotely programmed or managed by the grid operator. This remote-control capability allows the grid operator to rapidly and dynamically balance the grid so that supply consistently matches demand.

For example, during periods of high demand, the smart-grid operator could instruct DERs, such as battery storage systems, to discharge more power back onto the grid. Conversely, when there’s excess generation, the operator may command DERs, such as solar inverters, to curtail output.

The key point is that instead of simply placing these resources onto the grid, we must integrate them in a way that enables precise and coordinated control. With millions of small DERs supplementing a relatively small number of large rotating generators, fine-grained management becomes essential.

Examples of DERs include:

- The onboard charger in an electric vehicle

- EV charging stations

- Photovoltaic (PV) inverters

- Battery energy storage systems (BESS)

- Fuel-cell energy systems (ESS)

- Home energy management systems (HEMS)

The common characteristic of all DERs is that they can put power back on the grid. In some cases, like a BESS or EV, the DER can take power from the grid to charge its internal batteries and put power back on the grid in response to increased grid demand (Fig. 3).

As a DER, it must undergo not only functional testing, but also rigorous standards-based testing to ensure it’s a responsible and compliant “smart-grid citizen.”

Therefore, critical testing requirements for DERs include bidirectional power flow (e.g., vehicle-to-grid capability for EVs and EVSEs), interoperability standards, communication protocols that allow the grid to control the device, grid-interconnection functionality, and cybersecurity requirements.

The Final Word: Standards Must Be Followed

Grid modernization fundamentally depends on the effective management of DERs. Grid-code requirements feed into formal standards, which then translate into certification schemes.

Wikipedia defines a grid code as “a technical specification which defines the parameters a facility connected to a public electric grid has to meet to ensure safe, secure, and economic proper functioning of the electric system. The facility can be an electricity generating plant, a consumer, or another network. The grid code is specified by an authority responsible for the system integrity and network operation.”

Grid codes, therefore, set the rules for how DERs connect to the grid. For example, IEEE 1547-2018 is a grid code that establishes the rules and specifications for DERs. In support of 1547-2018, IEEE 1547.1-2020 is the testing standard that provides the "how-to" for testing via specific procedures and tests for DER equipment.

Then, UL 1741 SB is a certification standard that uses the IEEE 1547.1-2020 tests to verify compliance with performance requirements. Thus, UL 1741 SB is the official "product stamp" that certifies a device has successfully passed those tests and meets the requirements.

These standards are stringent, and grid operators will not permit any non-compliant or non-certified device to interconnect with the grid. Compliance isn’t optional. As a result, DER manufacturers must not only design and develop their devices, but they must also ensure those devices are certified in accordance with the relevant grid codes.

What’s Next?

In an upcoming article, I will explore home energy management systems, or HEMS. I’ll provide a clear definition, explain the benefits of deploying a HEMS, and consider the test challenges to ensure that the HEMS, as a DER, meets the required grid codes and functionality, as described in this article.

>>Download the PDF of this article

About the Author

Bob Zollo

Solution Architect for Battery Testing, Electronic Industrial Solutions Group

Bob Zollo is solution architect for battery testing for energy and automotive solutions in the Electronic Industrial Solutions Group of Keysight Technologies. Bob has been with Keysight since 1984 and holds a degree in electrical engineering from Stevens Institute of Technology, Hoboken, N.J. He can be contacted at [email protected].