Project Mercury and SpaceShipOne: Two Different Missions that Shaped the Space Race (Part 2)

What you'll learn:

- Although they served very different objectives and were separated by four decades of technological advances, the flights of NASA’s Faith 7 Mercury and XPRIZE Foundation’s SpaceShipOne were milestone events in the history of space exploration.

- Mercury capsules were hurled into space by repurposed ballistic nuclear weapons delivery vehicles, while SpaceShipOne’s first stage was a reusable high-altitude carrier plane.

- Despite their obvious differences, Mercury and SpaceShipOne shared several important elements that contributed to their missions’ success, including equal parts of competition, innovation, and a strong dose of piloting badassery.

Part 1 of this saga introduced the origins of the American space program and the Ansari X Prize, which carried its pioneering legacy onward four decades later. This concluding segment begins with a look at the two missions’ radically different approaches to launching their spacecraft before exploring the important role that the pilots’ skills and ingenuity played in their success.

Radically Different Launch Systems

The first two crewed Mercury flights were carried on their suborbital trajectories by human-rated derivatives of the Redstone ballistic missile1 (Fig. 1a). These rockets were based heavily on the technologies originally developed by Wernher von Braun for the V2 ballistic weapons that Germany used to bombard Britan during WWII.

Technologies included the use of a 75% alcohol/25% water fuel mixture and liquid oxygen (LOX) as its oxidizer. The V2’s design heritage was also evident in the construction of Redstone’s Rocketdyne A-7 motor, the turbopumps that fed it, and its simple but reliable LEV-3 autopilot system.

To achieve the velocities needed for orbital flights, subsequent missions were flown aboard an Atlas-D rocket, originally created to serve as an intercontinental ballistic delivery vehicle for nuclear weapons (Fig. 1b).

Powered by a pair of Rocketdyne XLR-85 engines burning kerosene and liquid oxygen that produced up to 360,000 pounds of thrust, the Atlas used super-thin fuel tank skins and other lightweight construction techniques to maximize its payload capacity.2,3 In fact, the stainless-steel skin of the early Atlas rockets was so thin that the rocket could not stand unsupported unless its fuel tanks were kept under positive pressure.

In contrast, Scaled Composites developed a low-cost alternative to conventional booster rockets for SpaceShipOne, in the form of a carrier aircraft dubbed the “White Knight.” Designed to serve as its “first stage” (Fig. 2), White Knight carried SpaceShipOne to nearly 60,000 feet before release. After dropping clear of the White Knight, SpaceShipOne’s pilot ignited its rocket engine and flew a steep ballistic trajectory toward space.

Propulsion was supplied by a hybrid rocket motor, built by SpaceDev, which burned a type of solid rubber (hydroxyl-terminated polybutadiene, i.e., HTPB), using liquid nitrous oxide as its oxidizer. The motor generated a peak thrust of 88 kN (20,000 lb.) during its burn that could last as long as 87 seconds.4

Although the carrier craft had a much longer wingspan (82 ft.) and was powered by a pair of GE J-85 afterburning turbojet engines, its twin boom tail assembly incorporated aerodynamic control surfaces that were very similar to that of SpaceShipOne. In addition, White Knight’s cabin, avionics, and trim system were virtually identical to its space-going counterpart.

>>Check out Part 1 of this series

Sharing so many identical components enabled the aircraft to serve as a flight qualification test bed for many of the critical components used to build SpaceShipOne. It also allowed White Knight to supplement the program’s computerized flight simulator,5 serving as a real-world tool to familiarize would-be astronauts with the spacecraft’s flight characteristics during the glide phase of its reentry.

By applying the technologies and frugal design philosophies it had mastered for earlier projects, Scaled Composites could build, test, and fly the first commercial spacecraft in 2004 on a tight budget, estimated at $20 to $30 million ($27 to $40 Million in 2024).3 In contrast, Project Mercury’s budget was estimated at $277 million (roughly $4 billion in 2024 dollars).6

The Human Factor and “Piloting Badassery”

Both programs’ success depended heavily on the skills, experience, and occasional bravery of their human pilots, especially when unexpected situations arose during their missions.

The Mercury program was punctuated with several incidents where the astronaut’s training and piloting skills helped them overcome severe technical problems that would have otherwise doomed their mission — and maybe their lives. The most striking of these occurred during the Mercury Atlas 9 mission, the final and longest flight in the Mercury program.

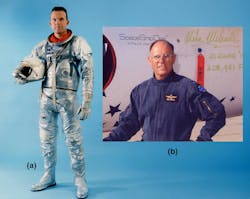

Piloted by Gordon Cooper (Fig. 3a), NASA planned the mission to last more than a day, roughly 3X the length of previous flights. To support the extended flight, NASA extensively modified Cooper’s capsule, dubbed Faith 7, adding larger batteries and oxygen tanks along with early versions of the freeze-dried foods that would sustain astronauts of the upcoming Gemini program during their multi-day missions.7

That changed at the beginning of its 19th orbit, about 29 hours into the flight. A short circuit in part of the craft’s power supply caused a complete failure of its automatic stabilization and control system (ASCS).

Without the attitude data produced by the ASCS’s gyro platform, neither Cooper nor Ground Control could perform the calculations needed to orient the capsule within the narrow parameters that would allow it to reenter the atmosphere without burning up or skipping helplessly back into space. Worse yet, the periscope that had served as a backup orientation system on previous missions had been removed from Faith 7 to save weight in the heavily laden vehicle.

In one of history’s greatest feats of piloting badassery, Cooper (with Ground Control’s help) determined the sight line of the horizon he’d see in his window when the craft was properly aligned and drew reference marks on the glass with a grease pencil. During his 22nd orbit, some 34 hours after liftoff, Cooper used the craft’s manual attitude controls to align it with the reference marks and then relied on his wristwatch to determine when to fire the retrorockets.

His engineering and piloting skills, along with his improvised recovery technique, resulted in a safe, and surprisingly precise, reentry that landed Faith 7 only four and a half miles from its recovery ship, closer than any computer-guided Mercury flight had achieved.8,9

Four decades later, SpaceShipOne’s first flight beyond the Karmen line also needed the quick reflexes and extraordinary skills of its pilot, Mike Melvill (Fig. 3b), to save it from disaster.

Although Melvill lacked the military experience enjoyed by most astronauts, his passion for aviation led him to earn multiple proficiency ratings, and eventually build his own aircraft, a VariViggen, coincidentally designed by Burt Rutan. The professional connection and admiration they developed led Rutan to hire Melvill as a test pilot for his homebuilt aircraft designs and, eventually, as chief test pilot for Scaled Composites.

On the Tier One project, Melvill played a major role in the rigorous test program that led up to SpaceShipOne’s historic suborbital flights. The program included a series of carefully sequenced unpowered and partially powered test flights that gradually explored the craft’s behavior across a wide range of speeds and altitudes.10

Despite these rigorous efforts, several unknowns remained, especially regarding the ship’s behavior during its steep supersonic ascent through the thin upper atmosphere.

Melvill discovered one of these invisible “gremlins” on June 24, 2004, during SpaceShipOne’s first attempt to fly to an altitude above 100 km (62 miles). Shortly after ignition, wind shear caused SpaceShipOne to experience a sudden unplanned 90-degree roll to the left.

Melvill’s initial attempts to correct the problem resulted in overshooting by 90 degrees to the right. Thinking quickly, he used a heavy application of the craft’s roll trim tab to level the ship out and proceed with the climb. Although this caused some secondary problems that persisted until the start of reentry, Melvill’s cool head and quick thinking helped keep the craft close enough to its planned trajectory to achieve an altitude of 328,491 feet (100,124 m). It was short of the plan’s 360,000-foot goal, but still enough to qualify Melvill as the world’s first commercial astronaut.2,4

Conclusions

Looking back through the 60+ years since the beginning of human spaceflight, it’s remarkable to note the common factors that enabled the success of the Mercury and SpaceShipOne programs. But perhaps the most important thing they shared was the pioneering roles they played in opening new horizons for human space exploration.

References

1. Loyd S. Swenson Jr., James M. Grimwood, and Charles C. Alexander, This New Ocean: A History of Project Mercury,” NASA SP-4201, 1966.

2. Andrew J. LePage, “Old Reliable: The story of the Redstone,” The Space Review, May 2, 2011.

3. Atlas (SM-65), Warren ICBM and Heritage Museum.

4. Scaled Composites, “Twenty years since breaking a boundary: SpaceShipOne,” June 2024.

5. Budd Davisson, “SpaceShipOne and Me: We Make a Couple of Digital Trips to Space in the SS1 Simulator,” Flight Journal, 2004.

6. General Dynamics, Flight Summary Report, Series D Atlas Missiles (Recovered from the Wayback Machine Archives).

7. Megan Garber, “2,060 Minutes: Gordo Cooper and the Last American Solo Flight in Space,” The Atlantic, May 2013.

8. Mercury-Atlas 9, NASA Space Science Data Coordinated Archive, NSSDCA/COSPAR ID: 1963-015A.

9. James M. Grimwood, “Project Mercury, A Chronology,” NASA Historical Branch, Manned Spacecraft Center, Houston, Texas, MSC Publication HR-1, NASA Special Publication-4001.

10 - Scaled Composites, Combined White Knight / SpaceShipOne Flight Tests (Recovered from the Wayback Machine Archives).

>>Check out Part 1 of this series

About the Author

Lee Goldberg

Contributing Editor

Lee Goldberg is a self-identified “Recovering Engineer,” Maker/Hacker, Green-Tech Maven, Aviator, Gadfly, and Geek Dad. He spent the first 18 years of his career helping design microprocessors, embedded systems, renewable energy applications, and the occasional interplanetary spacecraft. After trading his ‘scope and soldering iron for a keyboard and a second career as a tech journalist, he’s spent the next two decades at several print and online engineering publications.

Lee’s current focus is power electronics, especially the technologies involved with energy efficiency, energy management, and renewable energy. This dovetails with his coverage of sustainable technologies and various environmental and social issues within the engineering community that he began in 1996. Lee also covers 3D printers, open-source hardware, and other Maker/Hacker technologies.

Lee holds a BSEE in Electrical Engineering from Thomas Edison College, and participated in a colloquium on technology, society, and the environment at Goddard College’s Institute for Social Ecology. His book, “Green Electronics/Green Bottom Line - A Commonsense Guide To Environmentally Responsible Engineering and Management,” was published by Newnes Press.

Lee, his wife Catherine, and his daughter Anwyn currently reside in the outskirts of Princeton N.J., where they masquerade as a typical suburban family.

Lee also writes the regular PowerBites series.