What you'll learn:

- The Donut Lab battery announced at CES may be a real energy storage device based on pulling together some almost obscure details.

- The team of people involved on the research side, led by an Indian PhD, do seem to have the expertise to pull an energy storage device off, and a couple of hypotheses are presented about what it is and how could be made.

On Monday, January 5, 2026, Finnish Donut Lab revealed an "all-solid-state" battery with impressive parameters at CES 2026:

- 400-Wh/kg energy density

- Five-minute full charge

- Designed for up to 100,000 cycles

- Extremely safe

- Made of globally abundant materials

- Over 99% capacity retained at −30°C

- Lower cost than lithium-ion

From Monday onward, Donut Lab stirred up lots of excitement and lots of skepticism among battery experts by unveiling a production-ready, allegedly all-solid-state battery, claiming it's the first for OEM use.

The solid-state battery (SSB) is considered the Holy Grail of battery technology. Many companies are working on their development, but none have matched the parameters stated by Donut Lab. Why do SSBs receive so much attention?

Liquid vs. Solid Electrolyte

It’s believed that SSBs significantly improve safety over traditional lithium-ion batteries (LIBs) by replacing the flammable liquid electrolyte found in standard LIBs with a solid electrolyte material that replaces the liquid electrolyte and separator. Solid electrolytes can withstand much higher temperatures before decomposing, compared to liquid ones.

Solid electrolytes act as a physical barrier to block dendrites from growing through to the cathode and prevent short circuits, which may cause fires and destroy the battery.

Most of the liquid electrolytes have ionic conductivities of 2 to 12 mS/cm. A big breakthrough occurred in 2011 when lithium germanium thiophosphate (LGPS) was discovered. It has a room-temperature ionic conductivity of 12 mS/cm. LGPS marked the beginning of the era of so-called superionic conductors.

Since LGPS’s discovery, even more conductive materials have emerged, some of them reaching ionic conductivity of 40 mS/cm.

However, solid electrolytes struggle with their resistance to decomposition at both high (anodic) and low (cathodic) voltages, which is essential for performance, safety, and longevity. They face challenges from interfacial reactions with electrodes, particularly lithium-metal, and cathode materials, resulting in degradation and loss of capacity.

>>Download the PDF of this article

Many people believe that SSB will bring a significant breakthrough in energy density. This is true if lithium-metal or silicon anodes are used instead of graphite anodes, as lithium metal has about 10X the specific capacity of graphite: 382 Ah/kg compared to 3,860 Ah/kg.

Lithium-metal anodes can expand and contract by 15% to 30%, while cathodes usually show volume changes of 1% to 5%. These volume changes cause considerable mechanical stress, which can cause a disconnection between the electrolyte and the cathode, leading to fracturing and fatigue of the cathode.

So, are solid electrolytes good alternatives to liquid electrolytes in terms of ionic conductivity?

The devil is in the details. In traditional LIBs, the liquid electrolyte is present in all the pores of the active material of the cathode, which allows for efficient ion transport, but in the case of solid electrolytes, the ion transport is limited by the interface between the cathode and the solid electrolyte, and this is quite a problem (Fig. 1).

Finnish Your Donut

It’s important to know that Donut’s "all-solid-state" battery was likely not developed by Donut Lab. It was probably developed by Nordic Nano, another Finnish company founded in 2024. Donut is claimed to have made a significant investment in Nordic Nano in July 2025.

At CES 2026, Donut mentioned a 5-minute charging time and 100,000 charging cycles. Let's consider the best-case scenario test. It would take 5 minutes to discharge and another 5 minutes to charge this energy storage device. In total, it takes 10 minutes, and completing 100,000 cycles would require 694 days without stopping, which is nearly 2 years. If we consider realistic testing conditions, this test would take about five to six years. Does this suggest that the development of this battery finished five years back, before the founding of Nordic Nano?

Nordic Nano's LinkedIn profile says:

"Nordic Nano Group is a Finnish company manufacturing a new type of battery technology. The company's main products are solar panel coatings and non-toxic batteries made from the same material."

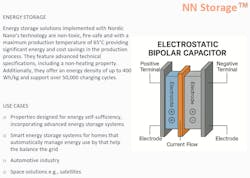

An excerpt from an online presentation by Nordic (Fig. 2) shows that its “energy storage” isn’t described as a SSB, but as an “electrostatic bipolar capacitor.” It lists parameters such as 50,000 cycles and 400 Wh/kg, which closely resemble the specifications of the Donut’s SSB at CES.

Esa Parjanen, the CEO of Nordic Nano Group, gave an interview in 2024 where he mentioned that solar panels and battery cells made from “nanomass” are twice as effective as standard solar panels.

Nano Nano

The solar panels are produced using nanoprinting technology, which utilizes expertise developed at the University of Eastern Finland (UEF). The second main component of Nordic’s secret sauce is a "nanomass" developed in Germany by Professor Holger Kohlmann at University of Leipzig. The material is a trade secret that the company doesn’t disclose.

This same mass appears to be used for nanoprinting of the battery cells that store electricity, produced by Nordic Nano Group. It replaces lithium, an element typically used in car and cell-phone batteries.

“These nanomass-based battery cells can withstand tens of thousands of charging cycles and can hold more energy. They are also fireproof and cannot explode.” — Esa Parjanen

Parjanen’s startup company aims to begin industrial mass production in Imatra (Finland) as early as 2026.

Nordic Nano had launched a pilot line at its Imatra factory in spring 2024, costing 20 million euros. Part of the amount was already raised, but part was missing.

So, this raises the question of who at UEF would have experience in processing German nanomass to make it suitable for printing batteries and solar panels?

A certain professor's name has already been mentioned on the internet, but I couldn't find any direct evidence of his involvement.

The Nordic Nano personnel page features six managers from retail and management, plus one person in communications, plus one researcher who is a chemist. In a small tech startup, it’s typical that every team member is involved in design or development. Have any of these six managers gained enough knowledge in two years to develop a top-tier battery?

The chemist, Bela Bhuskute, completed her undergraduate studies in India and then continued with postgraduate studies at the University of Tampere, where she defended her doctoral dissertation in 2025. Her dissertation was titled "TiO2-based Photocatalysts for Solar Fuel Production." I read her work, but there wasn't a single mention of using TiO2 (titanium dioxide) as a material for storage systems. The focus of this work is on how H2O can be photo-catalytically broken into H2 and oxygen (O2) using solar water splitting (SWS), which means it’s about hydrogen production.

Donut Secret’s Kryptonite

In my opinion, Nordic Nano's energy storage appears to be some kind of supercapacitor rather than a solid-state battery. Lots of mystery surrounds it, particularly the use of German nanomass in nanoprinting, which sounds quite enigmatic. But I do believe that it’s really the supercapacitor.

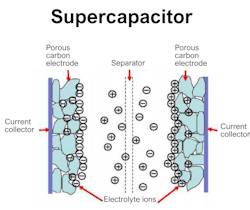

A supercapacitor's core composition includes highly porous electrodes (like activated carbon or graphene), a liquid or gel electrolyte (e.g., sulfuric acid, organic solvents), a porous separator (polymer film) preventing short circuits, and conductive current collectors (aluminum/copper) (Fig. 3).

Supercapacitor electrodes mainly utilize materials with a high surface area, such as activated carbon. It’s interesting to know that TiO2 in its amorphous form acts as a pseudocapacitive material, improving the surface of carbon electrodes of supercapacitors, boosting ion transport efficiency, rate capability, and interactions between the electrolyte and electrode. Now we know that there’s someone in Nordic Nano who has knowledge about TiO2.

The main difference between SSBs (rechargeable) and supercapacitors lies in their energy storage methods: Solid-state batteries rely on reversible chemical reactions (redox) to achieve high energy density by storing energy in chemical bonds, whereas supercapacitors utilize an electrostatic mechanism (electric double layer) for quick charging and discharging, resulting in lower energy density and minimal chemical alteration. It seems this work could go either way.

[Editor's note: A user on Reddit, "griding," in responding to someone posting this article, appears to me to have found the seminal paper, published by Korean researchers in January 2025, supporting Michael's hypothesis. S/he posted:

"I think I found the scienctific paper they based their tech on:

Nanocell CNT-PANI Composite Fibers

- The tech: A new fiber fusing Carbon Nanotubes and Polyaniline via strong chemical bonds.

- The record: Achieves 418 Wh/kg (Battery-level energy) while keeping 587 kW/kg (Supercapacitor power).

- The result: A flexible storage material that charges instantly, holds as much energy as a Lithium battery, and lasts over 100,000 cycles."]

Electrolytic Supercapacitor…or Battery?

I’d speculate, based on the tidbits that Michael has found, and the light bulb coming on as I prepared his article for publication as technology editor, causing me to look into all this a wee bit further, that Kohlmann’s research into the ionic conductivity of metal hydrides, like barium deuteride (BaD2), could form the basis for development of a solid-state electrolyte. Capacitors (non-polarized “electrolytic”) can use electrolytes, which is where Michael went with his hypothesis.

Couple Holger’s work with Nordic Nano Group’s Partner and Chief Scientist Bela Dhananjay Bhuskute’s prior work (I think her prior TiO2 research may be a distraction unless Michael has nailed it regarding the “battery” being a supercapacitor, though I think the Indian PhD’s work at high pressures is highly relevant) on atomic layer deposition (ALD) could mean that Nordic may have “printed” solid-state batteries, atom by atom, in the lab in Finland at UEF. UEF also has a pretty extensive computational modeling capability for thin films, led by Professor Tanja Tarvainen.

This makes me wonder if the grand claims of energy density, charge cycle life, and temperature range by Donut Labs are based on Bela’s possible post-molecular-modeling nano-battery measurements in the lab.

That could make sense in explaining the seemingly wild claims by Donut’s CEO for energy density, charge cycle life, and operating temperature range (semiconductor process developers have a keen understanding and awareness of temperature budgets). Then the devil would be in the details of scaling a few hundred angstrom-scale solid-state battery in a Finnish lab up to the size needed for a Chevy. Or a Verge motorcycle. A couple of months to show a “real” battery aligns with silicon wafer processing in progress.

Again, going back to Holger’s work, I’d postulate that he has developed the precursors for the metal hydride deposition (the so-called, “nanomass”), which is then deposited into possibly a graphene matrix using MOCVD, “microprinting.” If so, UEF has the computational modeling, and the semiconductor industry (companies like AIXTRON, Veeco Instruments, TNSC, and Thomas Swan) has equipment and knowhow that can scale up epitaxial layers to form a battery on 6-, 8-, or 12-in. silicon (relatively cheap) wafers.

I think printing these precursors onto an even larger substrate will be a trick and will require the more expensive polished wafers unlike the solar industry. But I’m not a process engineer despite holding a U.S. patent on a laser epi recipe on GaAs with my esteemed colleagues at the time at TriQuint (now Qorvo).

Then the question is whether production can keep up with the Verge motorcycle “production vehicle” run rate. At a bit over a million dollars in revenue last year, that’s about two or three Verge bikes a month, as a first order guess. Supplying batteries to a vehicle that’s “in production,” indeed. However, for exotic applications like satellites and other stuff that taxpayers pay for, if all this can be pulled off, call it good whether it’s really a battery or a supercapacitor.

Are materials like deuterium and barium scalable for global SSB demand for mobility applications? Doubtful. Lithium is a primordial element and is superabundant in the universe, and on this planet. Deuterium and barium? Not so much. Then again, it’s a thin film. — Andy Turudic, Technology Editor, Electronic Design

Donut or Do Nought?

In summary, exaggerated and overstated claims can be damaging. They create significant discomfort for scientists who are focused on the advancement of SSB and could make losers from them if their work has equivalent scaling problems.

Unless other scientists’ work is differentiating, this situation led by Donut Labs could unsettle investors and may backfire on the authors of these claims if they’re revealed to be misleading, severely damaging their credibility. While many have been accepting, a few have been dismissive. And there’s a possibility that an energy storage device could emerge from the Finns’ and Germans’ research collaboration.

Let’s hope we will soon see practical evidence of the specifications of this "storage system.” We’ve shown how it could be possible and what the limitations might be, as well as healthy caution and skepticism about bringing an SSB to the scale needed by the global transportation market. Readers’ theories and speculation are welcome in the comments section, below, in addition to taking our poll.

Andy's Nonlinearities blog arrives the first and third Monday Tuesday of every month. To make sure you don't miss the latest edition, new articles, or breaking news coverage, please subscribe to our Electronic Design Today newsletter. Please also subscribe to Andy’s Automotive Electronics bi-weekly newsletter.

>>Download the PDF of this article

About the Author

Michael Sura

IT/Electrotechnical and Energy Management Engineer

With ARUSCON, Michael Sura is an IT/electrotechnical and energy management engineer, board advisor & director, analyst, strategist, and author. He has energy knowledge and expertise, transportation expertise, and specializes in areas including Li-ion batteries, electromobility, and the green transformation.