NASA Library Closure: “Long Fuse, Big Boom”

What you'll learn:

- The impact of shuttering the NASA library on the industry in terms of the potential loss of years of research.

- The looming industry-wide economical impact of the closure.

By the time you read this, NASA will have closed its Goddard Information and Collaboration Center in Greenbelt, Md., effectively erasing 70+ years of technical and scientific knowledge as well as large chunks of the national space program’s history.

The government says that shuttering its largest research library will save roughly 10 million dollars a year in operating costs. However, the resources it contained produced orders of magnitude more in direct economic benefits to commercial aerospace and technology companies, not to mention the universities and other government agencies who it served.

This cost-cutting measure is only one of dozens of similar actions that fall into a class of actions sometimes referred to as “long fuse, big boom” decisions. Their effects won’t be noticeable immediately, but they have set in motion a series of long-term consequences that threaten to undermine a prime source of America’s prosperity, the health of its citizens, and its role as a global leader.

Library Closure Impact on NASA and Other Institutions

A recent story by the New York Times provides details on how the NASA library’s closure will affect the agency’s day-to-day operations. It also discusses the longer-term problems created by its sudden loss.

NYT reporter Eric Niiler explains “the directive gave Goddard Spaceflight Center’s Information and Collaboration Center 60 days to put a small portion of its 100,000 books and countless research documents and artifacts (many of them not digitized or available anywhere else) to long-term storage and consign the remainder for disposal. Besides the loss of decades worth of engineering and scientific data which has been frequently used to inform future projects, the library’s archivists must face painful decisions on what to do with information about experiments on NASA missions during the heyday of human space exploration and rare books from Soviet rocket scientists describing missions during the 1960s and 1970s.”

Niiler also reports that, in addition to disposing of its archives, “Specialized equipment and electronics designed to test spacecraft have been removed and thrown out, according to a statement posted on the website of the Goddard Engineers, Scientists and Technicians Association.”

Lessons Learned

In addition to their historic value for future generations, the lessons I learned while working in the aerospace industry strongly suggests that some of the lost equipment would have eventually found a second life as it was repurposed for future projects. It thus saves the millions of dollars it would have taken to build them from scratch.

Although it’s difficult to know which studies, records, and engineering data lost in this purge will be vital to future projects, I can tell you from personal experience that reconstructing this knowledge will be time-consuming and costly for both NASA and private industry.

Those lessons date back to the late 1980s, when I was working for General Electric’s Astro-Electronics Division (AED) (now a part of Lockheed Martin) on the Mars Observer interplanetary probe. The spacecraft we were building was commissioned by NASA to carry the first science experiments it would send to the Red Planet since the Viking landers back in the 1970s (Fig. 1).

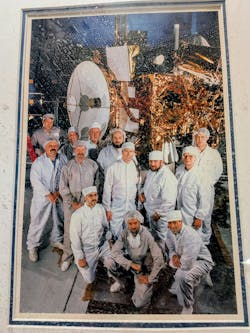

As part of the payload team (Fig. 2), I needed a lot of detailed information about what it would take to interface NASA’s experiments with our spacecraft — and to operate them successfully during its four-year mission. I was one of several people at GE who relied on the Goddard library’s records, which represented decades’ worth of experience in designing, building, and flying interplanetary spacecraft.

My quest included things such as the specifications for the space-rated electrical connectors we’d use for our payload interfaces, details on the data formats, modulation and encoding schemes our telemetry system would need to support, and the behavior of various materials during long exposures to the harsh conditions of deep space.

While we might have been able to eventually hunt down much of what we needed by visiting several other facilities, the archives were the only reliable source for some items. In addition to saving our project precious time and money, my visits to the archives gave me a chance to explore a bit of space history and make a few other surprising discoveries.

A Slice of History from “The Good Old Days”

One of the happy side benefits of my research was stumbling onto another nearby NASA archive that contained an extensive collection of photos taken by NASA, well as a large library of mission reports, all dating from before the Mercury program to the present day. A few of the photos helped me create the design of a commemorative t-shirt for the engineers, scientists, and others involved with the Mars Observer program.

The other treasure I discovered there was a shelf full of volumes on Lunar geology authored by Dr. Jacob Trombka, one of the NASA scientists who I worked with on the gamma ray spectrometer he’d be flying on our spacecraft. I was thrilled to read how my modest, unassuming colleague had already made space history 30 years before we met with his pioneering studies of lunar geology during the Apollo Missions.

Dr. T was a brilliant and extremely kind individual who touched my life in many ways. In addition to introducing me to the fascinating worlds of gamma ray spectroscopy and exogeology, he invited me to Washington to attend a meeting with Russian scientists. We were able to review the data produced by their PHOBOS probe during its recent exploration of Mars’ moon.

During a break in the proceedings, I had the privilege of acting as their tour guide during a visit to the Smithsonian Air and Space Museum. Even though the scientists were convinced that I was a CIA agent assigned to keep tabs on them, we reached a friendly détente as we bonded over our common love for the Star Trek TV series. But that’s another story for another time. Stay tuned...

The Importance of National Labs’ Research

Decades later, my second career as a tech journalist has reconnected me with NASA as I cover the important work being done there, and many of the nation’s other national labs, which contribute to America’s economy and its future. As a result, nearly every issue of my PowerBites blog includes at least one story about research on power-related technologies going on in places like the Pacific Northwest Research Laboratory, Sandia Labs, the National Renewable Energy Labs, and other national facilities.

Most of these federal facilities are structured to support a healthy mix of long-term basic research and near-term development, which is available for use in the public and private sectors. As a result, their relatively modest budgets provide remarkable returns as advances in everything from new types of semiconductors and battery chemistries to cleaner industrial processes are licensed and commercialized.

This pattern for success has been replicated throughout the economy as research from our national labs has helped drive advances in aerospace, pharmaceuticals, healthcare, and other critical industries. Meanwhile, research in agriculture, weather, geophysics, and related Earth sciences has enabled farmers to produce bigger, healthier crops, keep their livestock healthy, and cope with rapidly changing weather.

Consequences of the Cuts

While few politicians have considered how much these public investments have contributed to our nation’s economy and long-term growth, they’re about to find out as the consequences of the cuts they made begin to appear over the next year or two.

Farmers will be some of the first to feel them as the reductions in the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) budget, and the closure of the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR), compromise the accuracy of weather forecasts.

Those ill-conceived economy measures may also virtually eliminate any work to understand how long-term shifts in our climate or weather patterns will affect the regions that feed our nation. We can also expect the cost of meat to rise faster than inflation as diseases that affect our livestock evolve faster than the shrunken ranks of USDA scientists can track them.

These will be the first impacts of the closures to our nation’s wealth, health, and leadership, but they won’t be the last. In addition to the closure of important facilities, the remaining ones are undergoing a “brain drain” of intellectual capital, beginning with the loss of over 10,000 PhD-level employees involved with science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) or health-related fields who were pushed out of their jobs last year.

It will take decades to rebuild the teams of scientists who informed our healthcare system, driven innovations in aerospace technology, and performed invaluable fundamental research rarely undertaken by corporations operating in the private sector. The fuse has been lit on an explosive series of events that could destroy significant portions of our nation’s research infrastructure.

I invite your insights, questions and tales of your own encounters with national R&D facilities in the comments section below, or you can write to me directly by clicking here.

About the Author

Lee Goldberg

Contributing Editor

Lee Goldberg is a self-identified “Recovering Engineer,” Maker/Hacker, Green-Tech Maven, Aviator, Gadfly, and Geek Dad. He spent the first 18 years of his career helping design microprocessors, embedded systems, renewable energy applications, and the occasional interplanetary spacecraft. After trading his ‘scope and soldering iron for a keyboard and a second career as a tech journalist, he’s spent the next two decades at several print and online engineering publications.

Lee’s current focus is power electronics, especially the technologies involved with energy efficiency, energy management, and renewable energy. This dovetails with his coverage of sustainable technologies and various environmental and social issues within the engineering community that he began in 1996. Lee also covers 3D printers, open-source hardware, and other Maker/Hacker technologies.

Lee holds a BSEE in Electrical Engineering from Thomas Edison College, and participated in a colloquium on technology, society, and the environment at Goddard College’s Institute for Social Ecology. His book, “Green Electronics/Green Bottom Line - A Commonsense Guide To Environmentally Responsible Engineering and Management,” was published by Newnes Press.

Lee, his wife Catherine, and his daughter Anwyn currently reside in the outskirts of Princeton N.J., where they masquerade as a typical suburban family.

Lee also writes the regular PowerBites series.