Bioresorbable RFID Pill Backscatters That You’ve Taken Your Meds

What you'll learn:

- The importance and challenge of confirming that a patient has taken their pill.

- How an RFID tag and backscatter can be used to detect the pill’s presence in the gastric system.

- How coating the capsule with a dissolvable Faraday shield can delay backscatter activation until the pill is in the stomach.

- How to make the entire “assembly” bioresorbable and “go away”—with one tiny exception.

”Did you take that pill?” It’s a question often asked of patients with focus, memory, or distracting medical challenges. Yes, you can have one of those little containers with sections for each day’s pills, but that doesn’t fully answer the question.

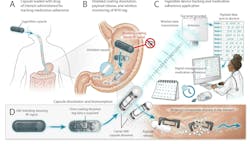

Now, a team at MIT has devised an RF-based solution. They designed and tested a pill that can report when it’s been swallowed via a backscatter RFID scheme. Dubbed SAFARI (Smart Adherence via FARaday cage And Resorbable Ingestible), the new reporting system can be incorporated into existing pill capsules. It contains a biodegradable radio frequency antenna—but with a twist.

To minimize the potential risk of any blockage of the GI tract, the MIT team decided to create an RFID-based system that would be bioresorbable, meaning that it can be broken down and absorbed by the body. After it sends out the signal that the pill has been consumed, most components break down in the stomach while a tiny RF chip passes out of the body through the digestive tract (Fig. 1).

What’s in the Capsule?

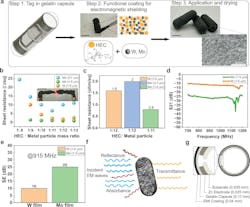

The ingestible platform consists of a zinc-based RFID tag, an RFID chip, a standard 000-size medical-pill capsule (26.1 to 26.2 mm closed length/9.5 to 9.9 mm diameter), a “payload” of interest (drug, sugar, dye, etc.), and a bioresorbable EMI-shielding material. The tag is incorporated into a standard medical gelatin or HPMC (hydroxypropyl methylcellulose) capsule along with the payload (the medication dose).

(Note that there have been previous efforts to develop RF-based signaling devices for medication capsules, but those were all made from components that don’t break down easily in the body and would need to travel through the digestive system.)

The overall tag includes a zinc antenna bonded to a cellulose acetate substrate using bioadhesive PGS (an elastomeric, biocompatible synthetic material), an RFID chip, and PLGA (a biodegradable, biocompatible, and FDA-approved copolymer) encapsulation. The electrical connection between the zinc antenna and RFID chip is maintained by wire bonding and supported with epoxy.

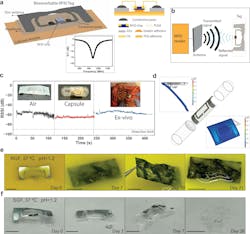

Once it’s encapsulated with ingestible EMI shielding coating, the tag signal is blocked, which is the OFF state. After a few minutes, the EMI shielding coating dissolves due to gastric acid and the tag is in the ON state. This allows the bioresorbable device to be queried from an external reader, confirming the ingestion.

The RF backscatter link uses a standard, off-the-shelf tag (Impinj Monza M700) that can be pre-programmed with information regarding drug dosage, manufacture date, serial number, and any other relevant information.

The zinc backscatter antenna is embedded into a cellulose particle. It’s “exposed” when the Faraday-shield coating layer around the capsule, which is made of cellulose and either molybdenum or tungsten, dissolves and unblocks any RF signal from being emitted.

The zinc-cellulose antenna is rolled up and placed inside a capsule along with the drug to be delivered. The outer layer of the capsule is made from gelatin coated with a layer of cellulose and either molybdenum or tungsten.

How Does the Capsule Work?

Once the capsule is swallowed, the coating breaks down, releasing the medical payload along with the RF antenna. The antenna can then pick up an RF signal sent from an external receiver and, working with the RF chip, send back a signal to confirm that the capsule was swallowed. This communication happens within 10 minutes of the pill being swallowed.

The EMI coating, capsule, and metal antenna components dissolve in the stomach. Due to the gastric acid, the zinc dissolves and is absorbed with the body while the RFID chip (a small biocompatible die) remains intact, making the overall system largely bioresorbable. The RF chip, which is about 400 × 400 µm, isn’t biodegradable and is excreted through the digestive tract. All other components would break down in the stomach within a week.

(In case you’re wondering or worried, the zinc antenna and molybdenum shielding are used in microgram–milligram quantities per capsule, and recognized to be orders of magnitude below levels associated with subclinical toxicity. Both elements are essential micronutrients with tightly regulated absorption and renal elimination. Prior animal and human studies demonstrate minimal risk of long-term accumulation or organ retention.)

The biodegradable signal-blocking shielding ink uses two components: a polymer matrix of 2-Hydroxyethyl cellulose (HEC) and bioresorbable metal fillers. It can be applied using a dip, brush, or spray coating. The RF performance of different formulations was tested from 700 MHz and 1.2 GHz using wideband near-field probes and a vector network analyzer.

Putting It to the Test

The backscatter link operates in the frequency range of 860 to 928 MHz. It was first tested “on the bench” to ensure that the received signal strength would be adequate at a distance of 20 to 30 cm when probed with a standard RFID reader at 30-dBm transmitted power.

Because a bench test alone is only a first step, they also tested RF performance with a gelatin capsule inside of an ex vivo (removed) swine stomach, as well as in vivo with a sedated swine. (They also tested for before-and-after levels of zinc and molybdenum in the blood; levels were negligible). Other tests involved rate of dissolving in stomach acid (Figs. 2 and 3).

Details of this project, including rationale, fabrication, materials, installation, tests, and results, are presented in their highly readable paper “Bioresorbable RFID capsule for assessing medication adherence” published in Nature Communications.

Reference

About the Author

Bill Schweber

Contributing Editor

Bill Schweber is an electronics engineer who has written three textbooks on electronic communications systems, as well as hundreds of technical articles, opinion columns, and product features. In past roles, he worked as a technical website manager for multiple topic-specific sites for EE Times, as well as both the Executive Editor and Analog Editor at EDN.

At Analog Devices Inc., Bill was in marketing communications (public relations). As a result, he has been on both sides of the technical PR function, presenting company products, stories, and messages to the media and also as the recipient of these.

Prior to the MarCom role at Analog, Bill was associate editor of their respected technical journal and worked in their product marketing and applications engineering groups. Before those roles, he was at Instron Corp., doing hands-on analog- and power-circuit design and systems integration for materials-testing machine controls.

Bill has an MSEE (Univ. of Mass) and BSEE (Columbia Univ.), is a Registered Professional Engineer, and holds an Advanced Class amateur radio license. He has also planned, written, and presented online courses on a variety of engineering topics, including MOSFET basics, ADC selection, and driving LEDs.