What Happens When Hyperscalers Take Their Foot Off the Accelerator?

What you'll learn:

- Why AI-driven hyperscaler spending is pushing memory spending into unprecedented conditions.

- How cloud provider capital-expenditure shows a growing uncertainty about the sustainability of the AI build-out.

- How the semiconductor cycles come into play.

The chip market is in an amazing place. All markets are growing, but two really stand out: memories and processors. But not just ANY memories and processors. DRAM, especially HBM DRAM, has been on a tear since 2024, which has created shortages of other types of DRAM, driving the prices up.

Meanwhile, NAND flash is beginning to enjoy a growing revenue surge that could lead to the market imitating DRAM and going into a significant shortage. As for processors, those that are doing best are GPUs and other AI-related processors like Google’s TPU, with server CPUs following along.

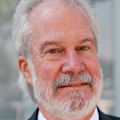

AI-Centric Markets Are Driving Record Growth

While other semiconductors are enjoying the kind of growth they had before the pandemic, GPUs, DRAM, and NAND flash are setting historic records. The difference between the growth of AI and non-AI semiconductors in 2024 is dramatically evident in Figure 1.

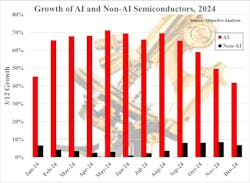

Why is that? It’s because hyperscalers are each trying to out-spend all others on AI. These companies have an enormous fear of missing out, and that’s led to the explosive growth of hyperscaler capital spending.

Figure 2 shows the incredible pace of this phenomenon, in which all major hyperscalers are participating. The handful appearing in this chart are those whose financials are easy to access, but others would add to this mix, too. The chart underscores such spending isn’t the result of one company’s quirks; rather, it’s something that’s being indulged in by the business at large.

Hyperscaler CapEx Surges, But This Has Troubling Implications

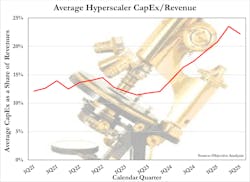

What’s been troubling Objective Analysis for quite a while concerns hyperscalers purchasing new plants and equipment faster than their customers’ AI spending has grown. How do you measure this? For that, we look at the capital spending above as a share of these companies’ growing revenues.

If we add together all of these companies’ revenues and divide it into the sum of their capital spending, we get their CapEx as a share of revenues. Corporate management runs companies according to their “Model,” and that model specifically states what percent of revenues will go to CapEx, how much to research, etc. to bottom out at the profit they hope to deliver.

Investors pay a lot of attention to this, and voice their objections to management if profits suffer because some or one of these segments gets an unfair share of revenues. The six companies in the chart have spent, on average, between 12%-15% of their income on CapEx — at least until AI capital spending took off in 2024. Then the percentage suddenly almost doubled to 25% (Fig. 3).

Although we haven’t gone deeply into this area, Objective Analysis suspects that management has convinced investors that they should take lower profits today for the promise of enormous benefits in the future. We haven’t yet added SG&A data to our model, but we believe that it’s being managed down to partly offset the capital spending increase.

Electronic Design readers are painfully aware of the fact that these companies have been laying programmers off, sometimes explaining that they’re giving these tasks to AI. I don’t know about you, but I’ve had numerous experiences with AI generating some pretty screwy results, so it doesn’t surprise me at all that the latest couple of updates to Microsoft Office introduced very visible new bugs into the code.

The AI Quotient

But, back to the topic at hand, why does this matter to the chip market? It’s because a sizable portion of this CapEx is being spent on AI semiconductors, which essentially means GPUs and HBM.

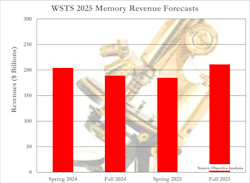

The companies participating in this have doubts just as we do at Objective Analysis. An easy way to tell is to look at the last four WSTS memory forecasts for 2025. The chart in Figure 4 below shows the 2025 revenue projection from the WSTS Spring 2024, Fall (Autumn) 2024, Spring 2025, and Fall 2025 forecasts. You can see that the forecasts go down and then back up again. This gives us some important insights, since it’s the leading memory companies’ view of the future. Here’s why.

WSTS produces its forecast by consensus: The companies who ship the product compare their forecasts and decide how to incorporate each company’s best ideas into the committee’s forecast. In the case of the WSTS memory forecast, all memory makers who participate in this exercise have had a chance to air their views and agreed to publish this number.

If you look again at the CapEx numbers in Figures 2 and 3, you’ll notice that the hyperscalers seem to be having second thoughts as well. Third-quarter capital spending, on the far right side of the chart, was roughly equal to second-quarter spending. It’s largely due to a sizable decrease from Microsoft, which seems to be more cautious than other very aggressive spenders. (Some companies follow their own best thinking, little influenced by the crowd, with Apple being a prime example.)

We now have two points: AI CapEx is driving companies to make risky investments, investments that their investors may start to complain about, and the hyperscalers, their suppliers, and some analysts are beginning to question whether this can or should continue.

What if the AI Semiconductor Investments Don’t Continue?

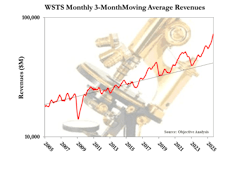

Figure 5 shows semiconductor monthly revenues, on a log scale (we use a log scale because this format shows constant growth as a straight line; in a standard linear format, it would take on the shape of a hockey stick), compared to the 3.9% average annual growth trend that these revenues have slavishly followed since 1996, or almost 30 years!

The left side of the chart shows how closely these revenues generally have followed the trend, with the noteworthy exception of 2008-9, during the global economic collapse. This caused a demand lapse, and such lapses were typically unusual enough that I would recite them and tell my audience that they occurred only every 15 years.

Then, in rapid succession, we had three demand cycles: a trade war scare that caused inventory builds and the 2018 cycle; then the COVID-19 pandemic, which resulted in another big cycle in 2022; and now we have AI driving another big cycle.

It doesn’t take much imagination to figure out that this cycle is likely to end with the market returning to the trendline as it did not only in the “up” cycles of 2018 and 2021, but also in the 2008 downturn. It’s something that the market has done repeatedly since 1996.

So, about that downturn: It's not a question of “if,” rather it’s a question of ”when?”

And what will occur as a result?

As a memory analyst I can tell you: When DRAM shifts from a shortage to an oversupply, prices collapse to cost in about two quarters, which in many past cases have been a 60% drop. That’s 60% in two quarters! It’s an unsustainable change.

The same mechanism impacts NAND flash as well. Economists call it “The Commodity Cycle.” Despite their leading-edge high-tech nature, DRAM and NAND flash are commodities. There’s an explanation of this on “The Memory Guy” blog.

Rough Seas Ahead in 2026?

Is 2026 the year of the downturn? It’s hard to tell. NVIDIA has done a wonderful job of lining up other customers to take up the slack if the hyperscalers decide to stop spending for a quarter or two. The most likely next one is various governments who have lots of money and are worried about “Data Sovereignty.” They don’t want some other country’s data center to be supporting their AI needs, hosting all of their national secrets.

But if hyperscalers decide to slow their AI spending in 2026, it’s highly likely that the memory market will collapse, and that GPU shipments will undergo a smaller-but-still-drastic decline.

Objective Analysis’ outlook for 2026 is negative, but with the understanding that we may be very wrong. We simply find it difficult to expect hyperscalers to keep up their current spending level. Instead, we believe that investor pressure will drive them to pause and wait for demand to catch up with supply. This will result in canceled memory and GPU purchases, which will hurt GPUs and ravage the DRAM and NAND markets.

The timing is hard to predict, but the outcome is unavoidable.

About the Author