Is It Make-or-Break Time for AI Processor Startups?

What you'll learn:

- How the AI processor startup boom is peaking and what the current landscape looks like.

- Where AI silicon innovation is happening, from wafer-scale engines for AI training to neuromorphic processors for inference.

- How many of the more than 100 AI processor startups could survive the shakeout and why NVIDIA is still holding onto its lead.

The explosive growth of NVIDIA and the insatiable demand for its GPUs have fueled a global surge in AI processors. However, the wave of startups building dedicated AI silicon has crested, or it’s very close to it.

The number of AI processor (AIP) startups around the world has more than doubled since 2016, and by the end of 2025, the number of standalone companies in the area jumped to an unsustainable total of 146. An astounding sum of $28 billion has been invested in these companies to date, with investors lured by the promises of the AIP market. Estimates are that the market will top $494 billion in 2026, driven mainly by inference (cloud and local) and edge deployments (wearables to PCs) for units, and training and hyperscalers for dollars.

That’s despite NVIDIA’s technology being backed up by a deep, wide, and all-but-unassailable software stack and a total hardware infrastructure for a data center. None of that seemed to sink in for investors, who have been ready and willing to invest in almost anyone who said they could build a faster, smarter, cheaper AI processor.

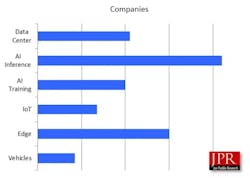

As might be expected, most companies are focusing on AI inference either in data centers or out at the edge. Training remains very capital-intensive, and most startups have ceded the space to NVIDIA.

“The population of standalone AI processor suppliers will shrink by 40% over the next year or two, and the reality could be worse than that.” — Jon Peddie Research

However, the window for most of these startups to succeed is likely closing. The peak formation year was 2018 (by then 75% of startups had already appeared). Interestingly, the rise in the number of startups began before NVIDIA’s business started booming, stunning the tech industry.

One would think that NVIDIA’s success was the honey that attracted all of the ants, but a good number (58%) of the startup companies got going before that. Since 2022, the sector has averaged seven acquisitions per year, and since 2020, 17 of the startups have filled an IPO.

The Complex Landscape of AI Chip Startups

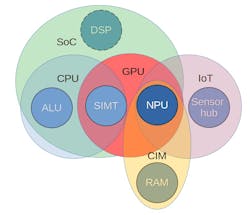

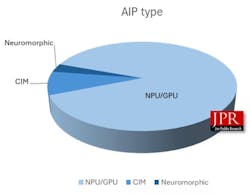

At a basic level, an AIP is a chip optimized to run neural-network workloads fast and efficiently by doing huge amounts of tensor math while moving data as little as possible. The processor types of offerings span GPUs, NPUs, compute-in-memory/processing-in-memory (CIM/PIM), neuromorphic processors, and matrix/tensor engines.

While CPUs and FPGAs are also used to run AI workloads, they tend to be evaluated separately from the $85 billion AI chip market since their generality makes it impossible to differentiate by function. But CPUs with vector extensions or SIMD engines (which is just about all of them) do fit in the AIP category as well. The overlap of CPUs, SoCs, and ASICs can be bewildering (Fig. 1).

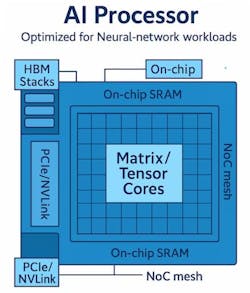

At a fundamental level, AI processors come with several core building blocks (Fig. 2):

- Compute blocks: Wide SIMD/SIMT cores (GPU style), tensor or matrix engines, (NPUs) vector units, activation units.

- Memory hierarchy: Small, fast on-chip SRAM close to the compute; larger HBM/DDR located outside the processor or in the same package; caches or scratchpads; prefetchers/DMA (CIMs loosely fit in this category).

- Interconnects: On-chip network-on-chip (NOC) and off-chip links, including (but not limited to) PCIe, CXL, NVLink, and Ethernet.

- Control: Command processors, schedulers, and microcode for kernels/collectives.

The world of AI processors spans cloud services, data center chips, embedded IP, and neuromorphic hardware. Founders and engineers address the gaps that CPUs and GPUs can't fill: managing memory; maintaining high utilization with small batches; meeting latency goals on strict power budgets; and providing consistent throughput at scale.

Companies develop products along two main dimensions: the type of workload — training, inference, or sensor-level signal processing — and the deployment tier, from hyperscale data centers to battery-powered and wearable devices.

Most technical work has centered on memory and execution control. CIM and analog techniques reduce data transfers by performing calculations within memory arrays and keeping partial sums nearby, which can lead to data-flow designs. Wafer-scale chips store activations in local SRAM and stream weights for long sequences.

Reconfigurable fabrics alter data flow and tiling during compile time to optimize utilization across multiple layers. And training chips emphasize interconnect bandwidth and collective communication, while inference chips prioritize batch-one latency, key-value caching for transformers, and power efficiency at the edge, as well as cloud independence to reduce latency (especially important in agentic robots).

Adoption depends on go-to-market strategies and ecosystem backing. Cloud providers are incorporating accelerators into managed services and model-serving frameworks. IP vendors are working with handset, auto, and industrial SoC teams, offering toolchains, models, and density roadmaps.

In addition, edge specialists release SDKs that compress models, quantize to INT8 or lower, and map operators onto sparse or analog units while achieving accuracy targets. And neuromorphic groups put out compilers for spiking networks and emphasize energy efficiency and latency on event streams. Refinements in compilers, kernel sets, and observability tools often outweigh peak TOPS.

Competition varies by tier (Fig. 3). Training silicon focuses on cost per model trained, considering network, memory, and compiler constraints. Inference silicon targets cost per token or frame within latency limits, using cache management and quantization as tools. Edge devices compete on milliwatts per inference and toolchain portability. IP vendors compete on tape-out time; power, performance, and area (PPA) goals; and verification support. Research projects balance speed to market against experiments that may alter the tradeoffs between memory, computing, and communication.

Throughout this process, teams customize designs to meet specific needs, such as attention depth, parameter count, activation size, sparsity, and precision policies. When companies synchronize silicon, compiler, and deployment tools, they reduce integration costs and speed up the transition from models to high throughput.

Customers then have multiple options: expand in the cloud, scale up with wafer-scale systems, embed NPUs in SoCs, or put computing closer to sensors using analog and neuromorphic chips. This vast volume of research and work is where the $28 billion investment is going, and what makes the startups attractive acquisition candidates (Fig. 4).

The End of the Explosive Growth of AI Chip Startups

But this “Cambrian explosion” in AI chip startups is likely coming to an end. In late 2025, the first signs surfaced of investors getting nervous about the huge capital equipment expenditures being made by hyperscalers, governments, and private firms, causing ripples in a stock market largely driven by the AI boom (Fig. 5). Talk about a bubble market and forecasts as to when it would pop filled the press.

Brewing just below the surface is the inevitable bubble pop in AI silicon providers. After all, no industry can sustain 146 suppliers.

There have already been several acquisitions and failures (21 by the end of 2025) and more will come. But VCs bet on the odds, and the odds are that the six companies each with more than $1 billion in funding will be the survivors, and the other 100-plus startups will be looking for a home in one of the 37 public companies in acquisition mode. The crystal ball at Jon Peddie Research suggests the population of standalone AI chip suppliers will shrink by 40% over the next year or two, and the reality could be worse than that.

Even though most of the startups will be acquired or fail, those that are acquired will bring a bonus of free IP with them, paid for by the enthusiastic and optimistic VCs. You can buy a lot of R&D with $28 billion, especially when the average employee count of the startups is less than 10 people. For reference, NVIDIA currently has around 36,000 employees, so it’s not exactly a fair fight.

These acquisitions will come with some broken hearts about what could have been. However, it's not merited if the premise of the dream was, “Build a better processor and the world will beat a path to your door.”

While NVIDIA’s dominance is backed up by the performance of its AI GPUs and deep software stack, its focus on building a total hardware infrastructure for a data center is keeping it ahead of the pack.

About the Author

Jon Peddie

President

Dr. Jon Peddie heads up Tiburon, Calif.-based Jon Peddie Research. Peddie lectures at numerous conferences on topics pertaining to graphics technology and the emerging trends in digital media technology. He is the former president of Siggraph Pioneers, and is also the author of several books. Peddie was recently honored by the CAD Society with a lifetime achievement award. Peddie is a senior and lifetime member of IEEE (joined in 1963), and a former chair of the IEEE Super Computer Committee. Contact him at [email protected].

James Morra

Senior Editor

James Morra is the senior editor for Electronic Design, covering the semiconductor industry and new technology trends, with a focus on power electronics and power management. He also reports on the business behind electrical engineering, including the electronics supply chain. He joined Electronic Design in 2015 and is based in Chicago, Illinois.