Top 10 Mistakes New C Developers Make: A Quick and Practical Guide

What you’ll learn

- Good C coding practices.

- Some patterns that ship, not vibes that occasionally (but not reproducibly) pass unit tests.

- Paying attention to details will make for fewer coding mistakes.

C gives you the kind of power that can build spacecraft or brick your laptop before lunch. This list isn’t a lecture; it’s a field guide to mistakes new developers make over and over. These are the bugs that can produce headaches — sometimes on-demand, sometimes nearly impossible to reproduce.

Such issues are particularly deleterious to teams in a sprint phase of development. The good thing is that many of them are so common whereby we can name them, shrink them, and give you habits that make your code boring in the best way: predictable across compilers, optimization levels, and platforms.

These tips can be used by anyone. There are also recommendations using standards like MISRA C/C++.

1. Off-by-one on strings: forgetting the NUL terminator

New C devs allocate “just enough” bytes for text — then write one more (Fig. 1). You size a buffer to n because the name has n characters, and boom: You forgot the NUL terminator needs a seat, too. That missing byte is the cause of many silent overflows and can turn log lines into memory corruption. It’s deterministic, repeatable, and, well, ugly.

Fix it like a pro: Always allocate length + 1 for C strings; prefer snprintf (not sprintf) and check its return, and use strnlen to cap reads. When in doubt, memset the buffer and assert that the last byte is 0 after writes. Rule of thumb: If you counted characters, add one; if you didn’t count, you should ask yourself why.

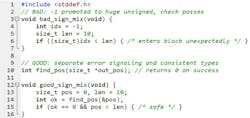

2. Signed/unsigned mix-ups that turn -1 into four billion

You compare an int (maybe -1 from a function error) to a size_t (array length), and the compiler promotes the int to unsigned, because — surprise! That’s what the C language spec says the compiler is supposed to do. Now your -1 just became 4,294,967,295 and your bounds check is now a red-carpet invitation to disaster (Fig. 2).

Deterministic, easy-to-reproduce, and maddeningly subtle. The fix: Keep sizes and indices in size\_t end-to-end; use explicit, narrow casts only at API boundaries; return errors via separate channels (distinct return codes) instead of negative sentinel sizes; and turn on -Wsign-compare. If you must mix, normalize first — validate that value ≥ 0 before converting to size\_t — and assert your assumptions. And for goodness sake, pay attention to warnings elicited by your toolchain. Warnings are bugs just waiting to “byte” you!

3. Thinking strncpy is “safe” and then shipping unterminated strings

strncpy feels like a life jacket, until you realize it doesn’t guarantee a NUL terminator when the source is too long (Fig. 3). You get a “safe” buffer that prints garbage, confuses parsers, and breaks strcmp. Worse, strncpy pads with zeros when the source is short, wasting cycles.

Do it right: If you need truncation with a terminator, use snprintf (and check the return). If you must use strncpy, immediately force-terminate: buf[n-1] = '0'. This is a simple rule to follow; don't slop together some scaffold code thinking that you’ll go back and fix it later — you probably never will...at least not until this bug is found out in the field.

>>Download the PDF of this article

4. Off-by-one loops that step past the buffer

Classic pattern: for (i = 0; i <= len; ++i) writes len+1 elements and clobbers the byte after the array. And guess what happens if your variable equals the maximum size it can hold? It produces an infinite loop (Fig. 4).

Good compilers must assume that this can happen, so using that structure cancels many handy loop optimization techniques. Deterministic, repeatable, and often crashes only on “just big enough” inputs. Use strict invariants: iterate i < len for element loops; i <= len only when indexing sentinel positions that you actually allocated. For NUL-terminated strings, stop on i < n-1 for writes, then set buf[i] = '\\0'. Add asserts on boundaries in debug builds.

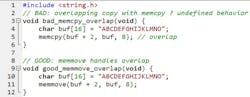

5. Using memcpy on overlapping ranges instead of memmove

memcpy assumes the source and destination don’t overlap. When they do, behavior is undefined and you get deterministic-looking corruption. Anytime you’re sliding bytes within the same buffer — deleting a prefix, inserting in-place — use memmove, which handles overlap correctly (Fig. 5). Rule: Same buffer + potential overlap → memmove; guaranteed non-overlap → memcpy.

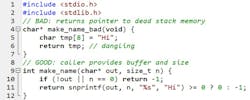

6. Returning a pointer/reference to a local variable

You create a buffer on the stack, return &buf[0], and — poof — the lifetime ends as the function returns. The caller now holds a pointer into dead memory; it “works” in trivial tests and then deterministically explodes (Fig. 6).

Fix: Have the caller provide the destination buffer and its size, or allocate with malloc and clearly document who frees. Rule: If it lives on the stack, it dies with the function — don’t hand out tickets to a ghost.

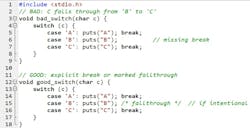

7. Missing break in switch → accidental fallthrough

You match the right case, then execute the next one, too, because you forgot break. Deterministic every run; sometimes hilariously wrong (Fig. 7).

Fix: End each case with break/return, or if fallthrough is intentional, mark it loudly with a “/* fallthrough */” comment and enable -Wimplicit-fallthrough. Bonus pro tip: Always add a default switch case, even if you think you’ve handled everything that can possibly come through the switch. Make that default do an assert. You might just surprise yourself when it trips.

8. Using sizeof on a pointer and thinking it’s the array length

You pass an array to a function; it decays to a pointer; sizeof(ptr) gives you 8 (or 4), not the element count. Cue under-allocations and half-copies — brutal (Fig. 8).

Rule: sizeof only knows the size of what it sees. Compute lengths at the point of declaration (sizeof arr / sizeof arr[0]) and pass the count alongside the pointer.

9. Mismatching allocation/free: new with delete[], malloc with delete

In C, the rule is simple: every malloc/calloc/realloc must be paired with exactly one free on the same pointer, from the same heap. Deterministic crashes come from freeing memory that wasn’t allocated, double-freeing or mixing custom allocators (Fig. 9).

Make ownership obvious; free in the same module that allocates, or document it loudly. As soon as you finish typing your malloc( ) line and press enter, type the corresponding free( ) line...then you can decide where the free needs to go.

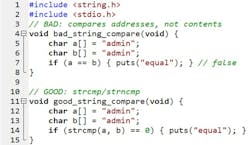

10. Comparing C strings with == and wondering why “admin” ≠ “admin”

In C, “string” variables are pointers. == compares addresses, not contents. Two identical-looking strings from different buffers will fail the == test every time, which is maddening (Fig. 10).

Use strcmp for full comparison, strncmp for bounded checks, and be explicit about case sensitivity (strcasecmp/strncasecmp where available). Rule: pointers point; they don’t prove equality.

Conclusion

Count your bytes, own your lifetimes, match your allocators, state your invariants, and let the tools yell early. Turn on every warning, use AddressSanitizer and Undefined Behavior Sanitizer in debug, add assertions where your logic pivots, and keep sizes in size_t from start to finish. Prefer patterns that encode correctness in plain C — pass lengths with buffers, wrap pointer+length in small structs, centralize ownership — so that the compiler and your reviewers can guard you.

Deterministic bugs are a gift; they teach fast if you listen. Build these habits now and your code will stop “surprising” you, reviews will go faster, and releases will feel less like roulette and more like clockwork.

MISRA C/C++ Poll

>>Download the PDF of this article

About the Author

Shawn Prestridge

Senior Field Applications Engineer/U.S. Field Applications Engineer Team Leader, IAR Systems

Shawn Prestridge is the U.S. Field Applications Engineer Team Leader for IAR Systems, where in addition to managing daily operations for his team, he trains customers and partners in using IAR’s products more effectively so that they can rapidly deliver embedded systems to the market. Shawn has worked with IAR for 12 years. He earned his degree at Southern Methodist University in Dallas, Texas.

Matthew Thoresen

Electrical Engineer, IAR Systems

Matthew Thoresen is an electrical engineer with a background in engineering design, embedded medical devices, and artificial intelligence. His work sits at the intersection of hardware, firmware, and AI, with a focus on building reliable, safety-minded systems that ship in the real world—not just live in a lab. He has worked on embedded platforms for medical devices, where safety, reliability, and regulatory constraints shape everything from system architecture to implementation.

Across projects, Matthew blends low-level embedded engineering with higher-level intelligent systems and automation, turning complex requirements into robust, testable solutions. He thrives in collaborative environments where clinicians, product leaders, and engineers come together to create devices that are not only innovative, but trusted in critical healthcare settings.

![Mismatching allocation/free: new with delete[], malloc with delete Mismatching allocation/free: new with delete[], malloc with delete](https://img.electronicdesign.com/files/base/ebm/electronicdesign/image/2026/01/6967e1ab1b86bfdcec7a32d7-fig_9.png?auto=format,compress&fit=max&q=45?w=250&width=250)