The First Color TV is Older Than You Think

What you'll learn:

- Insight into John Logie Baird and early television experiments.

- How Paul Nipkow’s scanning disc paved the way for mechanical television.

- Why electronic systems replaced mechanical television.

When people think of television, they often imagine today’s 8K flat screens or the bulky cathode-ray sets that weighed a ton. What some may not know is that, before those TVs became commonplace, there was a mechanical one — and at its center was Scottish inventor John Logie Baird.

He’s credited with giving the first public demonstration of a working television system on January 26, 1926, in London. His device, nicknamed the “televisor,” was clunky and low-resolution (Fig. 1), but it was the first time moving images had been successfully transmitted and displayed using a practical setup.

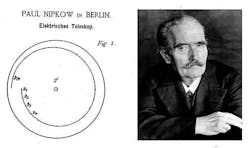

Baird didn’t invent television entirely from scratch. He took inspiration from other notable inventors, including German engineer Paul Nipkow, who patented the “Nipkow disc,” a rotating disk with a spiral of holes designed to break an image into sequential lines for transmission (Fig. 2).

Though he never built a working model, Nipkow’s principle became the foundation for early television experiments. Baird took advantage of Nipkow’s idea, adapting the scanning disc for both the transmitting camera and the receiving set.

By the mid-1920s, Baird developed these ideas into working demonstrations, and in 1924, he successfully transmitted flickering silhouettes. By the following year, he had advanced enough to capture recognizable human features.

“Stooky Bill”: First TV Star?

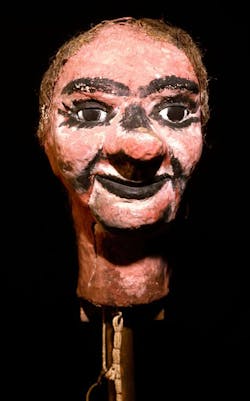

His early tests relied on a ventriloquist’s dummy named “Stooky Bill,” which tolerated the intense light levels needed for the photocells better than human volunteers (Fig. 3). With a resolution of only 30 lines and a frame rate of approximately 12.5 frames per second, the images were jerky and small, but they marked a significant leap forward in producing live, moving pictures.

On January 26, 1926, Baird invited members of the Royal Institution to his Soho laboratory, where he unveiled the world’s first public demonstration of true television. Attendees witnessed a live, moving image transmitted from one room to another, reassembled on a glowing screen via spinning Nipkow discs and neon lamps (Fig. 4). While primitive, the demonstration proved that television was possible and marked the official dawn of broadcast imaging technology.

Baird didn’t stop with black-and-white transmissions. By 1928, he was already demonstrating experimental color television using a disc segmented into red, green, and blue filters that reconstructed a three-color image.

That same year, he also achieved the first transatlantic television broadcast, transmitting signals from London to New York via shortwave radio. His inventive streak pushed mechanical television to its limits, even as electronic systems began to surpass them.

From Mechanical to Cathode-Ray TVs

Regardless of its pioneering status, mechanical television had its limitations. The moving parts were noisy, synchronization between transmitter and receiver was difficult, and the images were incredibly small and dim for mass entertainment.

By the mid-1930s, electronic television systems using cathode-ray tubes, developed by inventors such as Philo Farnsworth and Vladimir Zworykin, quickly overtook Baird’s mechanical approach. These newer systems offered sharper, steadier, and larger pictures, making them more practical for widespread broadcasting.

Still, Baird’s work remains a critical chapter in television history. His unique experimentation, often using improvised materials such as hatboxes, bicycle lamps, and tea chests, brought theory to life. By proving that images could be captured, transmitted, and received in real-time, Baird bridged the gap between imagination and implementation. As primitive as his system was, it laid the groundwork for everything that came after.

Mechanical television may have been short-lived, but it was the spark that lit the future of broadcasting. Without Baird’s ingenuity and the inspiration he drew from Nipkow’s earlier concepts, the leap to electronic television might have taken far longer. His demonstrations in the 1920s marked the moment when the idea of television stepped out of science fiction and into the real world.

About the Author

Cabe Atwell

Technology Editor, Electronic Design

Cabe is a Technology Editor for Electronic Design.

Engineer, Machinist, Maker, Writer. A graduate Electrical Engineer actively plying his expertise in the industry and at his company, Gunhead. When not designing/building, he creates a steady torrent of projects and content in the media world. Many of his projects and articles are online at element14 & SolidSmack, industry-focused work at EETimes & EDN, and offbeat articles at Make Magazine. Currently, you can find him hosting webinars and contributing to Electronic Design and Machine Design.

Cabe is an electrical engineer, design consultant and author with 25 years’ experience. His most recent book is “Essential 555 IC: Design, Configure, and Create Clever Circuits”

Cabe writes the Engineering on Friday blog on Electronic Design.