Tiny Spectrometer Features Tunable Layered Organic-Semiconductor Sensor

What you'll learn:

- The potential applications of a tiny optical spectrometer, and the challenges in developing one.

- How a unique, voltage-tunable, layered organic semiconductor offers a sensor solution.

- The performance achieved with this sensor and system.

For electrical engineers working in almost any part of the wired or wireless spectrum, the spectrum analyzer is a critical test and measurement tool. For optical engineering, the equivalent tool is the spectrometer, and it’s increasingly becoming a needed tool for EEs as electronics and optics interface, merge, and overlap.

Although wireless and optics both deal with electromagnetic energy, the reality is that their respective RF and optical bands have very different attributes and corresponding sensors. This is the case even as a key parameter of interest — the energy at each defined slice of the spectrum — is the same. Traditionally, a spectrum analyzer capable of working over a wide optical band with high resolution requires an arrangement of filters, gratings, and sensors that add to complexity and cost.

Mini Spectrometer Could Lead to Handhelds

New developments in materials are redefining that situation. Researchers at North Carolina State University successfully demonstrated a spectrometer that’s orders of magnitude smaller than current technologies and can accurately measure light from ultraviolet to the near-infrared wavelengths.

This technology makes it possible to create handheld spectroscopy devices and holds promise for the development of devices that incorporate an array of new sensors to serve as next-generation imaging spectrometers.

In addition to detailing their work as expected, the researchers thoughtfully provided an overview of the issues surrounding alternative approaches to tiny spectrometers and their tradeoffs (see sidebar “Tiny Spectrometer Challenges and Tradeoffs” below).

Tiny Spectrometer Challenges and Tradeoffs

The researchers noted that previous efforts to achieve miniaturization have been accompanied by degraded spectral resolution and operational bandwidth.

Several strategies have been used to scale down spectrometers for portable or integrated applications, including miniaturized dispersive optics, narrowband filters, Fourier transform-based systems, and computational reconstruction-based systems.

The first three strategies are challenging to scale to sub-millimeter dimensions due to optical-path-length limitations and the use of dispersive optics that make them difficult to make into imaging systems. Reconstruction-based systems can help reduce or eliminate the need for external optical elements.

Using arrays with spatial modulation typically requires more complex fabrication schemes and can suffer from reduced spatial resolution. Electrical modulation is able to achieve spectral reconstruction using a single pixel, but it requires time to modulate the detector responsivity. Nevertheless, this approach has the potential to be more compact and simpler to scale into imaging arrays as well as have faster detection speeds.

Demonstrations of miniaturized spectrometers using reconstruction approaches have been published using semiconductor nanowires, black phosphorus, 2D semiconductors, perovskites, and organic semiconductors. The devices based on black phosphorus, 2D semiconductors, and perovskites used an external voltage bias to achieve spectrally varied responses. However, these demonstrations have had limited optical bandwidth, detectivity, or linear dynamic range.

Fabricating reproducible 2D material devices can be a challenge, particularly when trying to realize detector arrays.

Organic Photodetector Key to New Approach

Noted by team leader and professor of mechanical and aerospace engineering Brendan O’Connor, “We have created a spectrometer that operates quickly, at low voltage, and that is sensitive to a wide spectrum of light.” He added that “our demonstration prototype is only a few square millimeters in size. This high-performance imaging spectrometers does not need for external gratings or filters.”

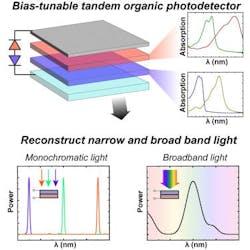

Key to this device is a tiny organic photodetector (OPD) with an active area of 7.6 mm2, capable of sensing wavelengths of light after the light interacts with a target material. Applying different voltages to the photodetector changes the wavelengths of light to which the photodetector is most sensitive (Fig. 1).

To scan the spectrum, a ramped control voltage is applied to the photodetector, which tunes its spectral response. The spectrometer unit then measures the output voltage during the ramping cycle, corresponding to the wavelengths of light being captured at each voltage. This yields enough data whereby a simple computational reconstruction using a measured spectral-response matrix can recreate an accurate signature of the light that’s passing through, or reflecting off of, the target material.

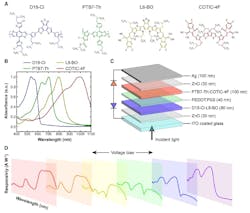

The spectrometer is based on an organic photodetector that leverages complementary spectral response of target organic semiconductors (D18-Cl, L8BO, PTB7-Th and COTIC-4F) in a “tandem cell” design. Each sub-cell is designed to have distinct absorption characteristics that overlap (Fig. 2).

The sub-cells have opposing polarity, which results in a bias-tunable spectral response that’s sensitive from ultraviolet to near-infrared wavelengths (400 to 1,000 nm). The bias tuning voltage is under 1 V, making this sensor compatible with battery-powered designs, while the entire tuning scan process takes less than a millisecond.

The front sub-cell and back sub-cell are fabricated with a common high-work-function interconnecting layer of poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) polystyrene sulfonate (PEDOT:PSS) and low-work-function electron transport layers (ETLs) of zinc oxide (ZnO) on the opposing sides of the cell. Finally, the electrodes consist of indium tin oxide (ITO) and silver for the front and back of the detector.

Test Results

The team assessed performance in different modes, including wideband and narrowband modes (Fig. 3). They used a high-performance commercial spectrometer as standard of comparison.

The detector demonstrated responsivity of 0.27 A/W, a rise/fall time of 2.82/3.72 μs, and optical detectivity of 1.4 × 1012 Jones. [The parameter "optical detectivity of ‘x’ Jones" refers to a specific unit of optical detector sensitivity called the Jones, which was defined in a paper by R.C. Jones. It’s a widely used measure of how well a detector can pick up a weak optical signal, and it’s defined as the reciprocal of the noise-equivalent power (NEP), normalized by the square root of the detector's area and bandwidth.]

The work is detailed in their readable paper “Single-pixel spectrometer based on a bias-tunable tandem organic photodetector” published in Cell Press—Device.

About the Author

Bill Schweber

Contributing Editor

Bill Schweber is an electronics engineer who has written three textbooks on electronic communications systems, as well as hundreds of technical articles, opinion columns, and product features. In past roles, he worked as a technical website manager for multiple topic-specific sites for EE Times, as well as both the Executive Editor and Analog Editor at EDN.

At Analog Devices Inc., Bill was in marketing communications (public relations). As a result, he has been on both sides of the technical PR function, presenting company products, stories, and messages to the media and also as the recipient of these.

Prior to the MarCom role at Analog, Bill was associate editor of their respected technical journal and worked in their product marketing and applications engineering groups. Before those roles, he was at Instron Corp., doing hands-on analog- and power-circuit design and systems integration for materials-testing machine controls.

Bill has an MSEE (Univ. of Mass) and BSEE (Columbia Univ.), is a Registered Professional Engineer, and holds an Advanced Class amateur radio license. He has also planned, written, and presented online courses on a variety of engineering topics, including MOSFET basics, ADC selection, and driving LEDs.