Thin-Film Cooler Doubles Solid-State Refrigeration Efficiency

What you'll learn:

- Why solid-state is an attractive proposition, in principle.

- How a new material offers far greater cooling efficiency and overall performance, along with manufacturing ease.

- The test results achieved using this new material approach.

The ability to provide active cooling to below ambient temperature on demand, as compared to just dissipation of excess heat, is one of the markers of the modern world. Consider that in the Paul Theroux novel The Mosquito Coast (1981), the protagonist proclaims, “Ice is civilization!,” as he attempts to bring a wood-fired refrigeration system to the Honduras jungle (the 1986 movie version starring Harrison Ford and Helen Mirren is also very good).

When you think about it, there’s a lot of truth and insight in that simple three-word exposition about the impact of refrigeration. The quest for better active cooling includes mechanically driven systems using fluid compression/expansion, solid-state thermoelectric coolers (TECs) such as Peltier devices, and other arrangements that leverage various thermal-physics principles (even Albert Einstein was fascinated by refrigeration and co-patented an innovative refrigerator design, see References below).

Novel Solid-State Thermoelectric Refrigeration System

Now, researchers at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory (APL), in conjunction with Samsung Research’s Life Solution Team, have created a new solid-state thermoelectric refrigeration system: It’s twice as efficient as devices built with standard bulk thermoelectric materials and presumed to be simple to manufacture as well. These gains were made possible through high-performance nano-engineered thermoelectric materials developed at APL, known as controlled hierarchically engineered superlattice structures (CHESS).

Bulk thermoelectric materials aren’t new — they’re already used in small products such as mini-refrigerators, localized component cooling, or optical transceiver temperature management. However, their low efficiency, limited heat-transfer capacity, and lack of compatibility with semiconductor chip manufacturing have restricted their adoption in larger, high-performance applications.

>>Check out this TechXchange for similar articles and videos

Leveraging CHESS Thin-Film Materials

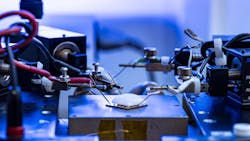

They used CHESS grown by metal-organic chemical vapor deposition (MOCVD) in the p-type Bi2Te3/Sb2Te3 materials system and n-type Bi2Te3/Sb2.7Se0.3 materials system (Fig. 1).

The researchers compared refrigeration modules utilizing traditional bulk thermoelectric materials with those using CHESS thin-film materials in standardized refrigeration tests in the same commercial refrigerator test systems, working with the Samsung team.

They validated the thermal modeling by quantifying heat loads and thermal-resistance parameters to ensure accurate performance evaluation under real-world conditions. Their objective was not only to assess performance at the “chip” level, but also to look at employing the devices at a module-sized cooling level.

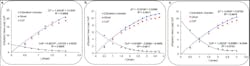

Using CHESS materials, the APL team achieved nearly 100% improvement in efficiency over traditional thermoelectric materials at room temperature (around 80°F/25°C) (Fig. 2).

They then translated these material-level gains into a nearly 75% improvement in efficiency at the device level in thermoelectric modules built with CHESS materials, and a 70% improvement in efficiency in a fully integrated refrigeration system (Fig. 3). Each represented a significant improvement over state-of-the-art bulk thermoelectric devices.

The figure of merit (ZT) for these thermoelectric materials is 100% better than the conventional bulk materials near 300 K. They also demonstrated module-level ZT greater than 75% and a system-level refrigeration ZT that was 70% better than that of bulk devices. These thin-film thermoelectric modules offer 100% to 300% greater coefficient-of-performance than bulk devices, depending on operational scenarios (Fig. 4).

Manufacturing Benefits of the CHESS Approach

The CHESS approach is also very attractive from the manufacturing perspective. First, the thin-film technology uses just 0.003 cubic centimeters of material refrigeration unit. This means APL’s thermoelectric materials could be mass-produced with semiconductor chip production tools, driving cost efficiency and enabling widespread market adoption.

In addition, the CHESS materials were created using the well-established MOCVD process, known for its scalability, cost-effectiveness, and ability to support large-volume manufacturing.

Will this become a commercial success for larger-scale refrigeration, or are there unanticipated real-world issues that get in the way? I don’t know, and it will be interesting to check back in a few years. If you’re interested, the work is detailed in their paper (with one of the most readable titles I have seen) “Nano-engineered thin-film thermoelectric materials enable practical solid-state refrigeration” published in Nature Communications.

References

“Einstein’s Little-Known Passion Project? A Refrigerator,” WIRED.

“The Einstein-Szilard Refrigerators,” Scientific American.

“Patent granted for Einstein-Szilard Refrigerator,” American Physical Society, November 11, 1930.

>>Check out this TechXchange for similar articles and videos

About the Author

Bill Schweber

Contributing Editor

Bill Schweber is an electronics engineer who has written three textbooks on electronic communications systems, as well as hundreds of technical articles, opinion columns, and product features. In past roles, he worked as a technical website manager for multiple topic-specific sites for EE Times, as well as both the Executive Editor and Analog Editor at EDN.

At Analog Devices Inc., Bill was in marketing communications (public relations). As a result, he has been on both sides of the technical PR function, presenting company products, stories, and messages to the media and also as the recipient of these.

Prior to the MarCom role at Analog, Bill was associate editor of their respected technical journal and worked in their product marketing and applications engineering groups. Before those roles, he was at Instron Corp., doing hands-on analog- and power-circuit design and systems integration for materials-testing machine controls.

Bill has an MSEE (Univ. of Mass) and BSEE (Columbia Univ.), is a Registered Professional Engineer, and holds an Advanced Class amateur radio license. He has also planned, written, and presented online courses on a variety of engineering topics, including MOSFET basics, ADC selection, and driving LEDs.