Infineon and Flex Assemble the Building Blocks of a Zone Controller

What you'll learn:

- What's inside Infineon's and Flex's modular dev kit for zonal control units?

- Differences between domain and zonal architectures.

- How the zonal controller operates.

In the software-defined vehicle (SDV) era, cars are rapidly becoming data centers on wheels, with centralized software replacing fragmented hardware that’s too inflexible to be updated wirelessly.

To stay on top of the software complexity, automakers are rewiring the hardware under the hood into “zonal architectures.” Here, controllers once tailored to specific domains — for instance, the powertrain, infotainment, or safety — are now location-based, reducing the wiring between them and latency with it. Zone controllers take control of the sensors, actuators, and other peripherals within the zone, and they act as gateways, connecting to other zones and the central vehicle computer.

By replacing lots of single-function MCUs with more potent and programmable CPUs, zonal controllers can consolidate many of the electronic control units (ECUs) in the vehicle, which helps simplify power and signal transmission. They tend to have more than enough performance to run predictive diagnostics and other complex applications that are impractical or impossible with ECUs. Additional headroom also gives automakers the ability to upgrade the software within them using over-the-air (OTA) updates.

To fast-track the development of new zonal architectures, Infineon Technologies said it teamed up with electronics manufacturing giant Flex to roll out a modular development kit for zonal control units (ZCUs).

The companies said FlexZoneX features 30 unique building blocks, covering all of the key components for data routing, power distribution, and load control in a ZCU, tied together with Flex’s design and integration expertise. These “reusable” assets can be scaled up or down depending on the vehicle, giving engineers a faster and more flexible way to tailor the performance, size, and cost of the ZCU to their specific needs.

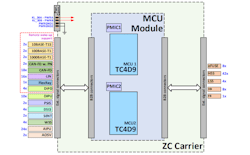

At its core are two of Infineon’s high-performance, six-core TC4x MCUs. These automotive-grade MCUs feature high I/O density and computational power, which are both critical in high-end zone controllers. The dual-MCU solution comes with a wide range of connectivity and networking technologies, including Ethernet, so that it can work as a gateway. It also features smart power switches to enable more intelligent power network management.

The platform launched at CES, formerly the Consumer Electronics Show, in Las Vegas.

What are the Differences Between Domain and Zonal Architectures?

As software becomes a bigger differentiator in cars, automakers are under pressure to upgrade the hardware beneath it. They aim to reduce the explosion of ECUs that has come to define traditional “domain” architectures.

In the domain approach, which is often used by legacy automakers, every related set of functions in the car — whether powertrain, infotainment, chassis, active safety, or body control — is managed by its own domain controller. They communicate with one another via gateways.

Instead of distributing functions over many discrete ECUs, the domain controller sits above them all. With the help of a hypervisor, functions can even run as software applications on the same MCU, consolidating several smaller ECUs into one.

This architecture allows the hardware to be tailored for the specific domains, and it helps simplify the complexity of the ECUs that can’t be fully replaced by software. However, as the number of new features in cars and the amount of software underpinning them grows, things have been getting over-complicated. These domains require multiple networks made up of numerous localized point-to-point connections crisscrossing the vehicle to bridge the gaps between various domains (Fig. 1).

As modern cars take on more complex tasks, these architectures also create redundant power and data connections between domains. It results in a web of wiring that stretches into every corner of the car, leading to costly, space-consuming cable harnesses. That can lead to more hops through the network, which causes unnecessary complexity and performance degradation. Despite the consolidation offered by domain controllers, cars built this way can still carry as many as 150 ECUs, each with its own wiring.

To dial down the complexity, upstarts such as Tesla and Rivian are rewiring the electric and electronic (E/E) architecture of the vehicle into zones. This divides the vehicle into physical zones — for instance, east, west, north, and south — each managed by a local controller, typically located near the hardware it serves.

Zonal controllers link sensors and other nodes that are in physical proximity, even when they belong to different domains. The zones then link directly to one another and to a central computing node over the Ethernet backbone, ultimately reducing latency.

One of the benefits derived from this architecture is decoupling hardware from software development, diminishing the complexity of both. For example, Rivian reconfigured the adaptive suspension in its latest electric truck to a zonal architecture: The south zone is linked to the rear actuation components, with the west zone interfaces located in the front suspension. The system is then coordinated over a network bus. In contrast, a legacy automaker would typically use a single, suspension controller with every component wired directly into it.

By localizing computation and connectivity, zonal designs remove more of the heavy, costly wiring that once stretched into every corner of the car and cut down on the total amount of hardware.

Rivian’s latest zonal architecture, for instance, reduces the number of control modules from 17 in its first-generation truck to seven. The ones that remain are optimized for infotainment, autonomous driving, and battery management, among others. The savings come out to around 1.6 miles of internal wiring. The company claims a 20% reduction in material costs.

Zonal controllers typically rely on high-performance, multicore MCUs. It enables them to consolidate functions from multiple domains while preserving the isolation needed to run “mixed-criticality” workloads with different safety requirements.

Infineon predicts approximately 50% of all new vehicles will have adopted a zonal architecture by 2030.

Connect, Power, Control: The Do-It-All Zonal Controller

Within each zone, the zonal controller acts as a local gateway (Fig. 2). This is a complicated role, requiring it to connect, control, and power a wide range of different sensors and other systems to the broader power distribution system and in-vehicle network (IVN).

The Flex-built platform will allow OEMs to realize well over 50 power distribution, 40 connectivity, and 10 load-control channels for rapid evaluation of zonal architectures and early application development.

By giving access to these building blocks in a single unit, Infineon said its customers can “right-size” the design depending on the situation while preserving feature headroom for future models. The flexibility enables you to start with the full “superset” of hardware and then whittle it down to optimize for cost.

The zone controller comes with a relatively large amount of space for software applications as well as the ability to be updated over time. Each high-performance MCU is equipped with up to 10 MB of SRAM memory and up to 21 MB of NVM.

To seamlessly connect with the rest of the vehicle, the zonal controller provides six Ethernet channels via integrated Brightlane PHYs, including two 1000BASE-T1 interfaces. These allow connections to the central compute node and another ZCU at the same time, with one interface upgradable to 2500BASE-T1. Two additional 100BASE-T1 Ethernet channels support high-bandwidth connections to other zone controllers, while Ethernet can also be used to connect two sensors using the 10BASE-T1S standard.

The FlexZoneX comes with a wide range of more traditional automotive interfaces, too. Among them is a pair of CAN-FD interfaces with networking that enables specific ECUs on the network to wake up while other others remain on standby, reducing overall power use. In addition, it offers 18 CAN-FD channels to connect a wide range of ECUs spread out around the vehicle, with support for up to 16 LIN connections.

The new unit enables all essential zone control functions, including secure data routing with hardware accelerators, memory partitioning for seamless software updates (also called A/B swap), and security. It also comes with overcurrent, overvoltage, and I2T protection, along with capacitive load switching and reverse polarity protection. Infineon said its AURIX MCUs are surrounded by its OPTIREG power supply, PROFET smart power switches, and MOTIX motor-control solutions, among other products.

The smart power switches are designed to act as eFuses, which will replace traditional fuses, reducing wiring and enabling automakers to implement more intelligent and efficient power network management.

Check Out More CES 2026 Articles

About the Author

James Morra

Senior Editor

James Morra is the senior editor for Electronic Design, covering the semiconductor industry and new technology trends, with a focus on power electronics and power management. He also reports on the business behind electrical engineering, including the electronics supply chain. He joined Electronic Design in 2015 and is based in Chicago, Illinois.