Physical AI's Push Shifts into High Gear

What you'll learn:

- What is physical AI and how does it extend edge AI running on embedded hardware?

- Why hardware/software co-design is vital for engineers working with physical AI.

- Where physical AI is headed, from autonomous cars to industrial robots.

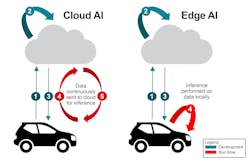

For a long time, AI models have had their heads in the cloud. Traditionally, these models have been trained and run inside data centers, and they could not directly affect the physical world. But as AI accelerators matured, edge devices started running models locally, capturing data close to the source to enable lower-latency inference. However, the output of those models still required direct human interaction to manifest in a physical action.

Today, innovations in safety, security, and reliability have made it possible for advanced driver-assistance systems (ADAS) in cars and industrial robots to act safely without humans in the loop. These innovations are helping AI transition from being a digital assistant that informs decisions to AI that can not only sense and think, but also act. This is where physical AI, sometimes referred to as embodied AI, comes into play.

But as the shift to physical AI accelerates, a question emerges: How do we ensure these capabilities become broadly accessible, not limited to only the most advanced or high-performance systems?

What is Physical AI?

The term physical AI refers to AI models that run on embedded hardware and directly influence a system’s physical behavior.

Physical AI isn’t an entirely new concept. It pushes the concepts of edge AI and real-time control into systems that not only interpret their environment locally, but also use that interpretation to shape physical motion.

Figure 1 helps illustrate the difference between physical and edge AI. In a humanoid robot — one of the flagship physical-AI applications — physical AI is used to control the robot as it grabs and lifts a box, while edge AI covers the capabilities of the processors that locally run AI models.

Consider a driver approaching traffic that slows unexpectedly on a busy highway. Today, the vehicle’s deterministic systems respond when the distance to the car ahead shrinks to a defined threshold, slowing the vehicle with the aim of stopping safely.

A physical-AI system changes when that happens. It analyzes emerging traffic patterns earlier and adjusts speed even before the defined threshold would have been crossed. The result is a smoother, more controlled change in motion enabled by the AI running directly on embedded hardware in the car. This sort of improvement is even more impactful when it can appear in many vehicles, not just a few.

Every millisecond matters when AI analyzes and reacts to sensor and actuator data in real-time. Physical AI fills the need for local, near-instantaneous processing.

>>Download the PDF of this article

However, we still use massive amounts of computing and memory in the cloud to train and refine physical-AI models. For instance, digital twins are critical when it comes to training physical-AI models, including those used in robotics. By building a virtual version of a system, complete with its mechanics, electronics, and sensors, we can test and refine models before they interact with hardware.

Where Edge AI Ends and Physical AI Begins

Edge AI covers AI models that run locally on everything from smaller microcontrollers (MCUs) to embedded processors, pooling and processing data from sensors and then generating outputs without relying on remote servers. The concept is outlined in Figure 2.

What distinguishes physical AI is what happens after the model produces its output. Edge AI can classify an image, identify a sound, or interpret sensor data. Physical AI brings together perception with actuation to control how a system moves, reacts or adjusts in real-time. For instance, a car can react further ahead of time when physical AI interprets multiple cues from nearby traffic locally, supporting smoother changes in speed.

In the industrial world, warehouse robots are able to adjust their routes as people move near them because onboard models process the scene without network delay. Industrial equipment can fine-tune the torque, position, or speed of motors when local models evaluate sensor data continuously rather than deferring to AI models running in the cloud.

None of this is new. Engineers have used predictive and even machine-learning models in embedded systems for years. But physical AI stands apart by integrating these capabilities at a deeper level into system designs, where local inference and actuation are tightly coupled. Because physical AI is being woven into a wide range of product families and at varying price points, engineers need approaches to hardware and software that scale.

Physical AI Hinges on Hardware/Software Co-Design

Physical AI generally breaks down into three fundamental parts: sense, think, and act. For instance, a self-driving car “senses” its surroundings using cameras, radar, LiDAR, and other sensors; “thinks” by processing data to plot out a safe path on the road ahead; and, finally, “acts” by controlling the steering, brakes, and throttle to execute the plan. Traditionally, AI models are used to sense and think about the surrounding world. But when AI models start to control movement, it changes the rules of system design.

In physical AI, engineers can no longer rely on constant wireless connectivity because these systems require predictable timing, accurate sensor data, and hardware that can respond in a matter of milliseconds.

Engineers face a mix of hardware and software design considerations. For instance, processors must be able to execute models within the timing requirements of the control loop, while the sensor chain must be able to deliver accurate, dependable data. Software needs to coordinate perception and actuation without introducing latency, and verification becomes more complicated, as errors now carry real-world consequences for reliability of the machinery and safety of the user.

Hardware and software shape each other in physical AI far more than in prior generations of embedded systems. As a result, physical-AI development is best approached as a co-design effort, in which hardware and software decisions are treated as tightly connected. A practical example helps illustrate the point.

Consider a small robotic arm designed to handle delicate components on a production line. The software team may want to deploy a larger model to improve grasp prediction, but that has implications for the hardware team, since the processor must still run inference within a tight control loop.

Conversely, the hardware team may want to adopt a new type of current sensor inside the motor to deliver higher-resolution data. That, in turn, pushes the software team to adjust the model and control logic so that the arm can take full advantage of the improved signal quality.

Through coordinated co-design, both sides of the engineering team can come to a solution where the AI model fits the compute budget, the sensors support the needed precision, and the control loop stays within its timing window. This ultimately allows the arm to move in a safer, more reliable way.

Hardware is Hard in Physical AI Systems

Semiconductors are the foundation for physical AI. These systems rely on embedded processors that run the AI model, signal-chain devices that capture sensor information with accuracy, and power technologies that maintain stable operation as loads shift. Each of these parts sets the limits for timing, precision, and consistency in a physical-AI design.

What I’ve seen in many designs is that improvements in one area ripple into others. A new sensing chain can enable more precise control. A processor that supports a slightly larger model can help a robot handle more complex scenarios. And a refined power architecture will help systems maintain consistent performance during rapid movements.

Fundamentally, physical AI depends on this interaction between components in terms of predictable processing, reliable sensing, and stable power systems.

Where is physical AI headed? I’m seeing trends across the industry that are shaping how physical AI systems take form. Designers are bringing sensing, computing, and control closer together to support predictable timing and consistent performance.

As discussed, simulation and digital-twin environments are increasingly common in development flows, giving teams a way to test behavior before hardware is available.

Today, physical AI is gaining momentum across several sectors:

- In buildings and infrastructure, engineers can build controllers to adjust mechanical systems based on environmental information.

- In robotics, onboard intelligence helps machines adjust their movement around people and equipment.

- In industrial automation, equipment adapts behavior based on live sensor input, helping processes stay stable under changing conditions.

In all of these situations, semiconductor companies like Texas Instruments play a vital role in shaping what physical-AI systems can accomplish. That’s because their performance, accuracy and reliability depend on the underlying hardware — not only software.

Ultimately, they’re the ones supplying the building blocks of the physical-AI era. And as these technologies spread into more types of devices and new tiers of products, their job is also to make sure these capabilities remain within reach for as many designers as possible.

If physical AI is to shape how machines move, react, and support us, improving safety and convenience, it must be broadly available on everyday devices and not just limited to high-performance systems.

>>Download the PDF of this article

About the Author

Artem Aginskiy

General Manager, Jacinto High-Performance Compute, Texas Instruments

Artem Aginskiy is the general manager for Jacinto microprocessors focused on Edge AI products in automotive and robotics. He received a master of science in Electrical and Computer Engineering from The Georgia Institute of Technology.