Laser, Radar, Comb, and Enhanced Atoms Yield Precise THz Measurement

What you'll learn:

- The challenges of terahertz-band components and frequency measurement.

- How a sophisticated combination of optical and electronic components representing advanced principles are being used to measure terahertz frequencies with high accuracy and resolution.

- How this arrangement leverages commercially available components to simplify and speed the experimental implementation.

Terahertz-band electromagnetic energy is finding an increasing number of applications, yet efficient generation and detection remain a challenge. Thus, it’s an active area of research. That space in the spectrum, generally considered to be from 0.1 to 10 THz (100 to 10,000 GHz) occupies a huge bandwidth swath between traditional microwaves/millimeter waves and the optical spectrum. Development of suitable components and circuits in this region has been stymied for technical and physics reasons.

Despite (or perhaps due to) the technical impediments, terahertz-band projects are attracting considerable R&D and product interest. Its electromagnetic energy can penetrate many non-metallic materials, such as plastics, paper, and textiles, and they’re absorbed by water and organics. In turn, it offers non-ionizing, safe methods for imaging, sensing of biomolecules, scanning, and more.

We’re also seeing developments, techniques, and technologies of the optical world “spill over” into, and be leveraged by, the terahertz regime.

Quantum Antenna

However, the precise detection of weak and narrowband terahertz signals is fairly difficult. Now, a team from the Faculty of Physics and the Centre for Quantum Optical Technologies at the Centre of New Technologies of the University of Warsaw (Poland) has introduced a new way to measure hard-to-detect terahertz signals using a "quantum antenna."

They do this with a novel type of single-photon detector based on Rydberg atoms to both detect and calibrate a terahertz-frequency comb over an octave span. The scientists applied an innovative radio-wave detection setup that not only senses terahertz radiation, but also accurately calibrates a frequency comb in the targeted part of the spectrum range. And it does so with megahertz-level resolution.

Rydberg Atoms

With Rydberg atoms, one electron is excited to a very high energy level (principal quantum number n), making them unusually large (micrometer scale), sensitive to electric fields, and possessing strong interactions. Named after Swedish spectroscopist J. R. Rydberg, who first characterized their properties, they behave somewhat like giant hydrogen atoms with exaggerated properties and are used in quantum technologies for sensing and computing.

You may have seen some of the ways in which optical combs are being used already to enable, among other applications, high-precision optical and frequency metrology. Optical-frequency combs are well known in the optical domain as a revolutionary development (a word that should not be used casually but is justified here). They’re now standard for precision measurement in atomic clocks, spectroscopy, and more. In fact, it was recognized through the award of the 2005 Nobel Prize in Physics to their developers.

Now, pulsed terahertz sources that generate electromagnetic frequency combs have emerged as powerful tools to address these challenges in the terahertz, non-optical range of the spectrum. The new approach combines two key methods: Autler-Townes splitting measurements, which allow for precise determination of the terahertz electric field strength in absolute units, and a microwave-to-optical conversion technique, which extends the sensitivity down to the level of thermal radiation.

Autler-Townes Splitting Measurements

Autler-Townes (AT) splitting measurements use a strong coupling laser to split an atomic or quantum system's energy levels, thereby creating a “doublet” whose frequency separation (the AT splitting) is proportional to the electric field or Rabi frequency. (The Rabi frequency is the frequency at which the probability amplitudes of two atomic-energy levels fluctuate in an oscillating electromagnetic field. It’s proportional to the transition dipole moment of the two levels and to the amplitude of the electromagnetic field.)

To achieve this, they employed a gas of rubidium atoms prepared in a Rydberg state. These "swollen" atoms act as a quantum antenna that’s extremely sensitive to external electric fields. In addition, by using tunable lasers, the detector can be adjusted to respond to one specific frequency within such a field, across a range that extends up to terahertz waves.

Not surprisingly, calibration and measurement confirmation has been a big challenge with terahertz waves. A major advantage of using Autler-Townes splitting to measure the electric field is that the measurement result depends only on fundamental atomic constants, providing an absolutely calibrated readout. Unlike classical antennas, which require laborious calibration in specialized radio laboratories, the atomic-based system is, in a sense, a standard unto itself.

Hybrid Terahertz-to-Light Conversion for Extreme Sensitivity

However, their core method has a limitation: On its own, it’s not sensitive enough to record very weak terahertz signals. To overcome this problem, the research team additionally applied a radio wave-to-light conversion technique invented at the University of Warsaw and adapted it to the needs of terahertz radiation.

In this process, the weak terahertz signal is converted into optical photons, which can then be detected with immense sensitivity using single-photon counters. This hybrid approach is the key to success. It combines the extreme sensitivity of photon detection with the ability to "recover" the calibration capabilities of the Autler-Townes method, even for the weakest signals.

The sensor based on Rydberg atoms possesses all of the features needed to perform precise frequency-comb calibration. It can be tuned to a single tooth of the comb and then retuned to the next tooth, and the next. The scientists managed to observe several dozen teeth in a very wide frequency range this way. Furthermore, thanks to the knowledge of the fundamental properties of atoms, the comb was directly calibrated, precisely determining its intensity.

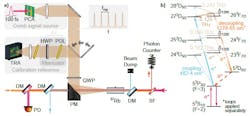

The experimental setup is quite complicated, as you would expect (Fig. 1).

There are two noteworthy observations in this arrangement:

- First, they used a standard off-the-shelf automotive radar chip, the TRA_120_045 from Indie Semiconductor,1 as their calibration reference. This is a very good example of how innovators adapt and use low-cost, commercially available devices from apparently unrelated applications so that they don’t have to make their own or “reinvent the wheel.” Thus, it speeds their project and minimizes possible headaches.

- Second, they used commercial PCA (photoconductive antenna), here the BATOP iPCA-21-05-300-800-h,2 a broad-area interdigital, GaAs-absorber, photoconductive terahertz antenna with a micro-lens array that emits terahertz pulses when pulsed by a femtosecond laser.

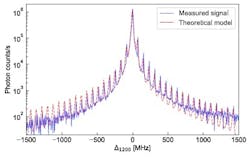

Many perspectives are available to assess their results. One of these is shown in Figure 2, with the resolution of the tunable broadband readout of the frequency comb around 125 GHz.

References

1. Indie Semiconductor FFO GmbH (formerly Silicon Radar), TRAˍ120ˍ045 120-GHz Wide-Band IQ Transceiver with Antennas on Chip (actual range is 114 GHz ~ 134 GHz)

2. BATOP GmbH, iPCA-21-05-1000-800, broad-area interdigital photoconductive THz antenna with micro-lens array for laser-excitation wavelength ~ 800 nm

About the Author

Bill Schweber

Contributing Editor

Bill Schweber is an electronics engineer who has written three textbooks on electronic communications systems, as well as hundreds of technical articles, opinion columns, and product features. In past roles, he worked as a technical website manager for multiple topic-specific sites for EE Times, as well as both the Executive Editor and Analog Editor at EDN.

At Analog Devices Inc., Bill was in marketing communications (public relations). As a result, he has been on both sides of the technical PR function, presenting company products, stories, and messages to the media and also as the recipient of these.

Prior to the MarCom role at Analog, Bill was associate editor of their respected technical journal and worked in their product marketing and applications engineering groups. Before those roles, he was at Instron Corp., doing hands-on analog- and power-circuit design and systems integration for materials-testing machine controls.

Bill has an MSEE (Univ. of Mass) and BSEE (Columbia Univ.), is a Registered Professional Engineer, and holds an Advanced Class amateur radio license. He has also planned, written, and presented online courses on a variety of engineering topics, including MOSFET basics, ADC selection, and driving LEDs.